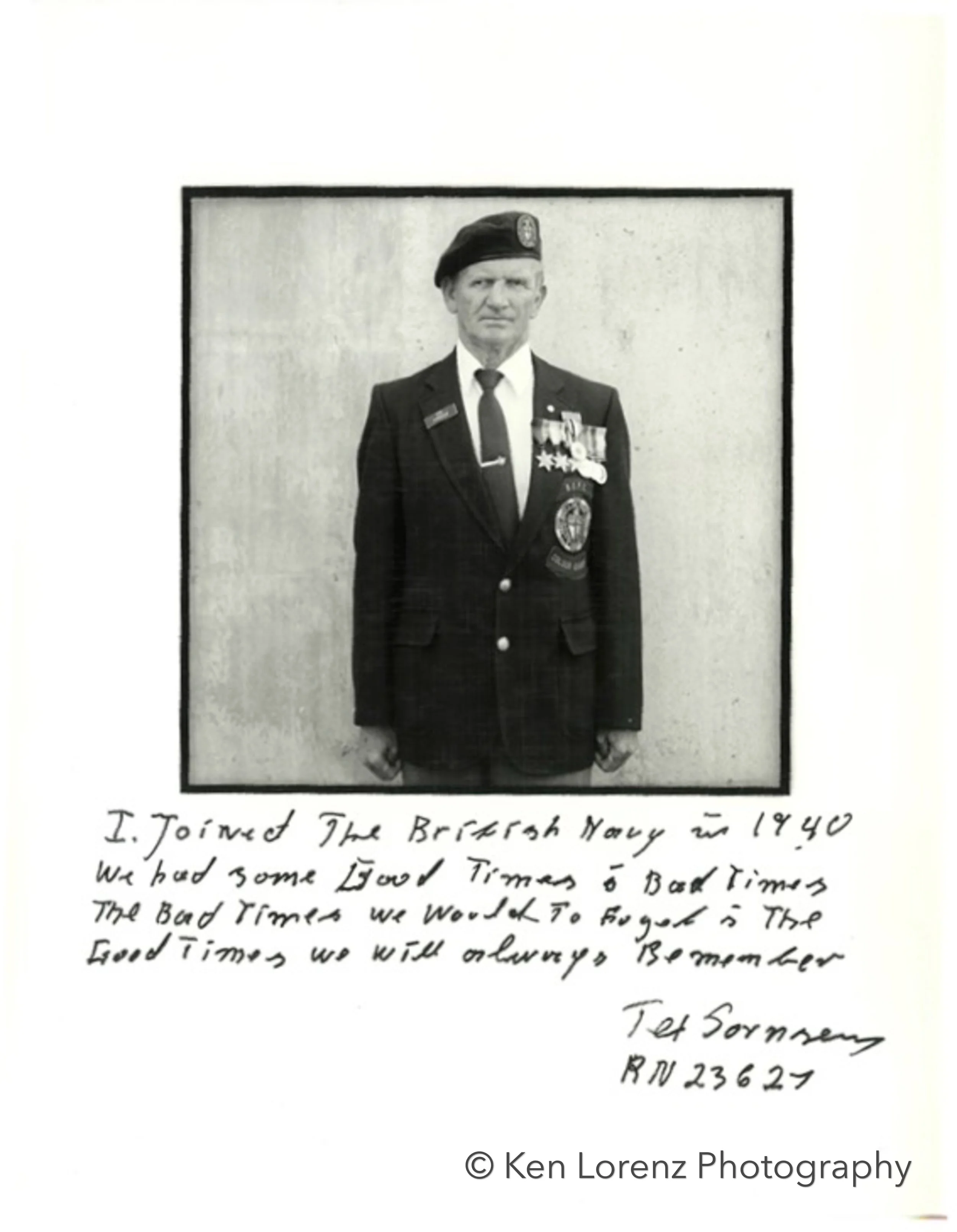

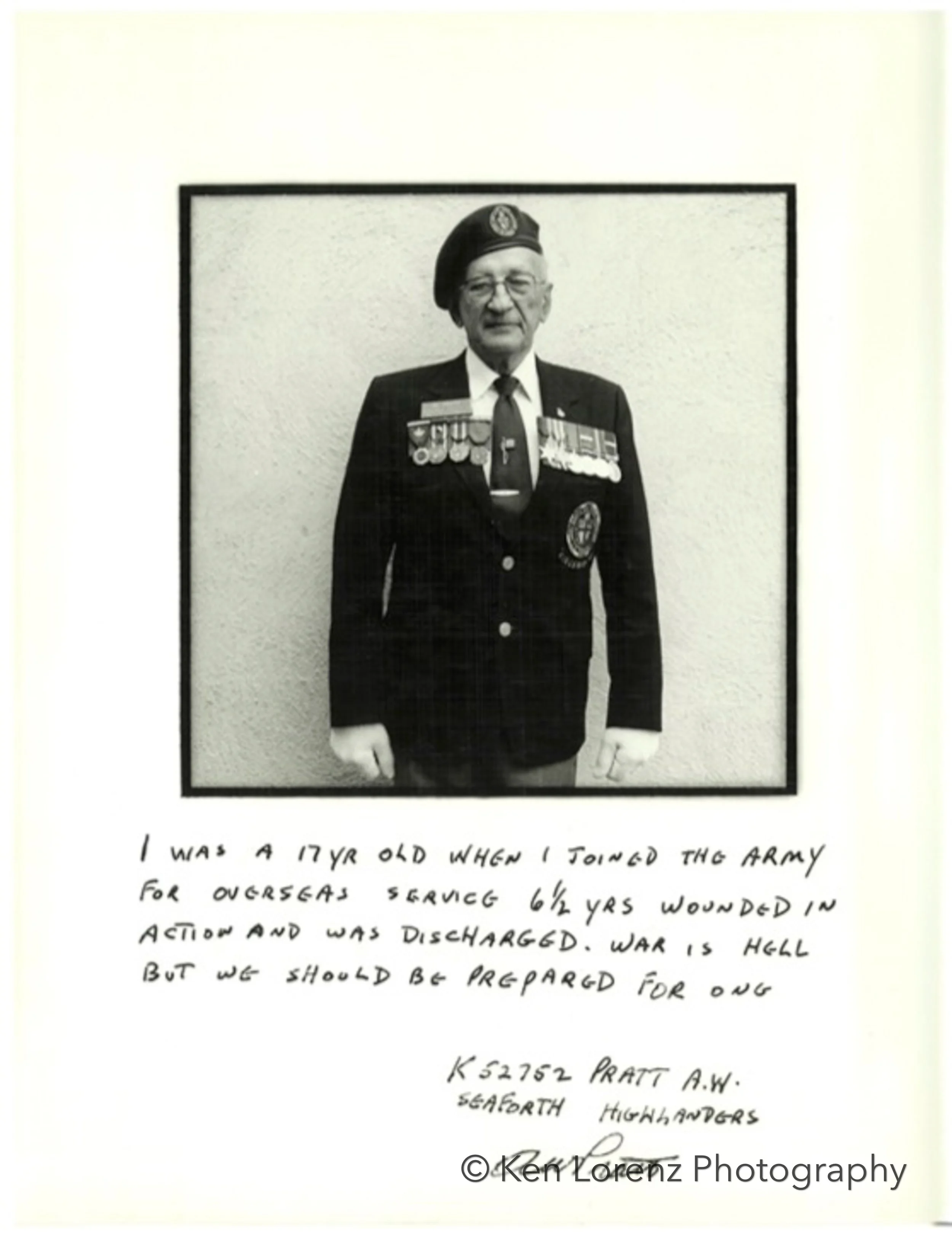

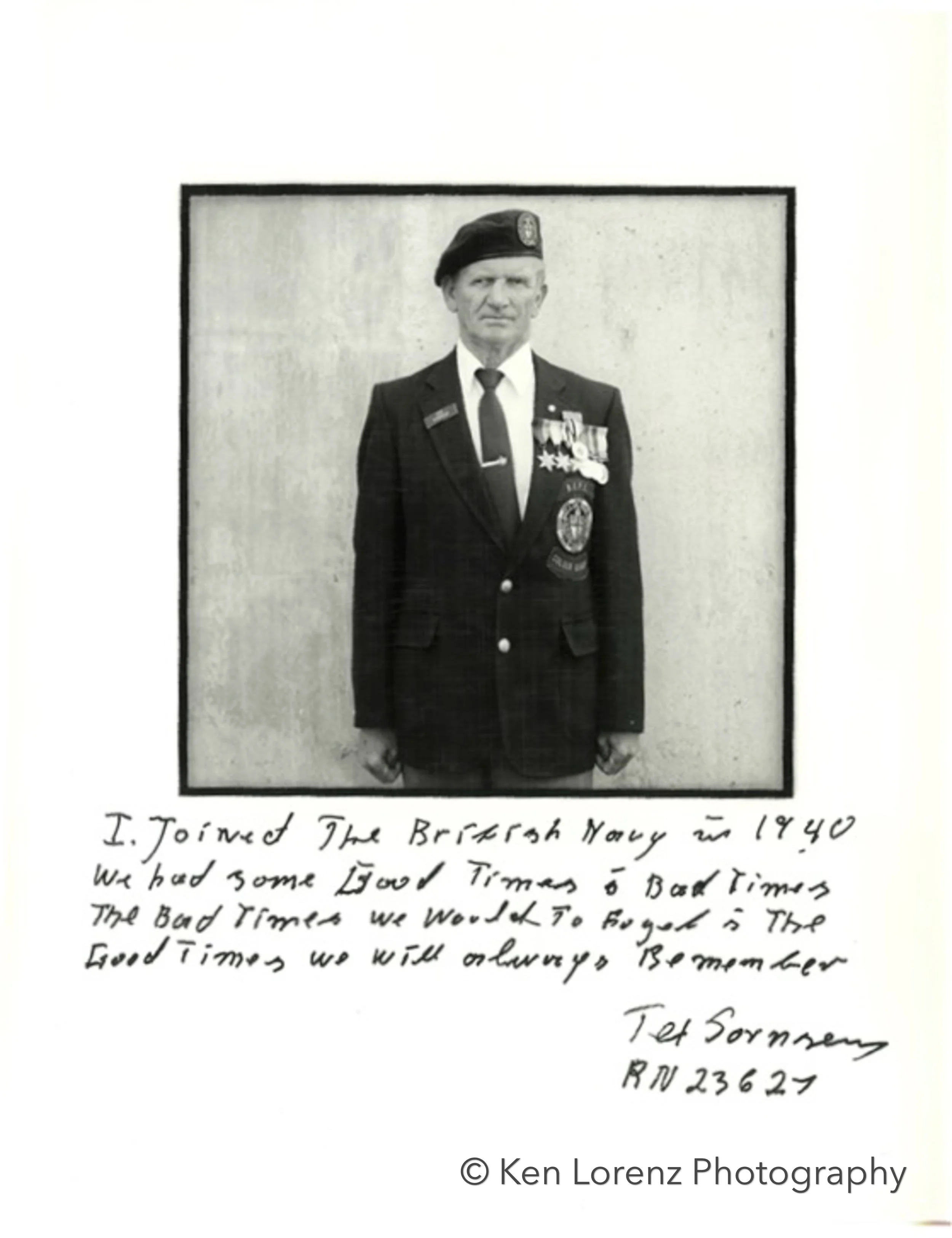

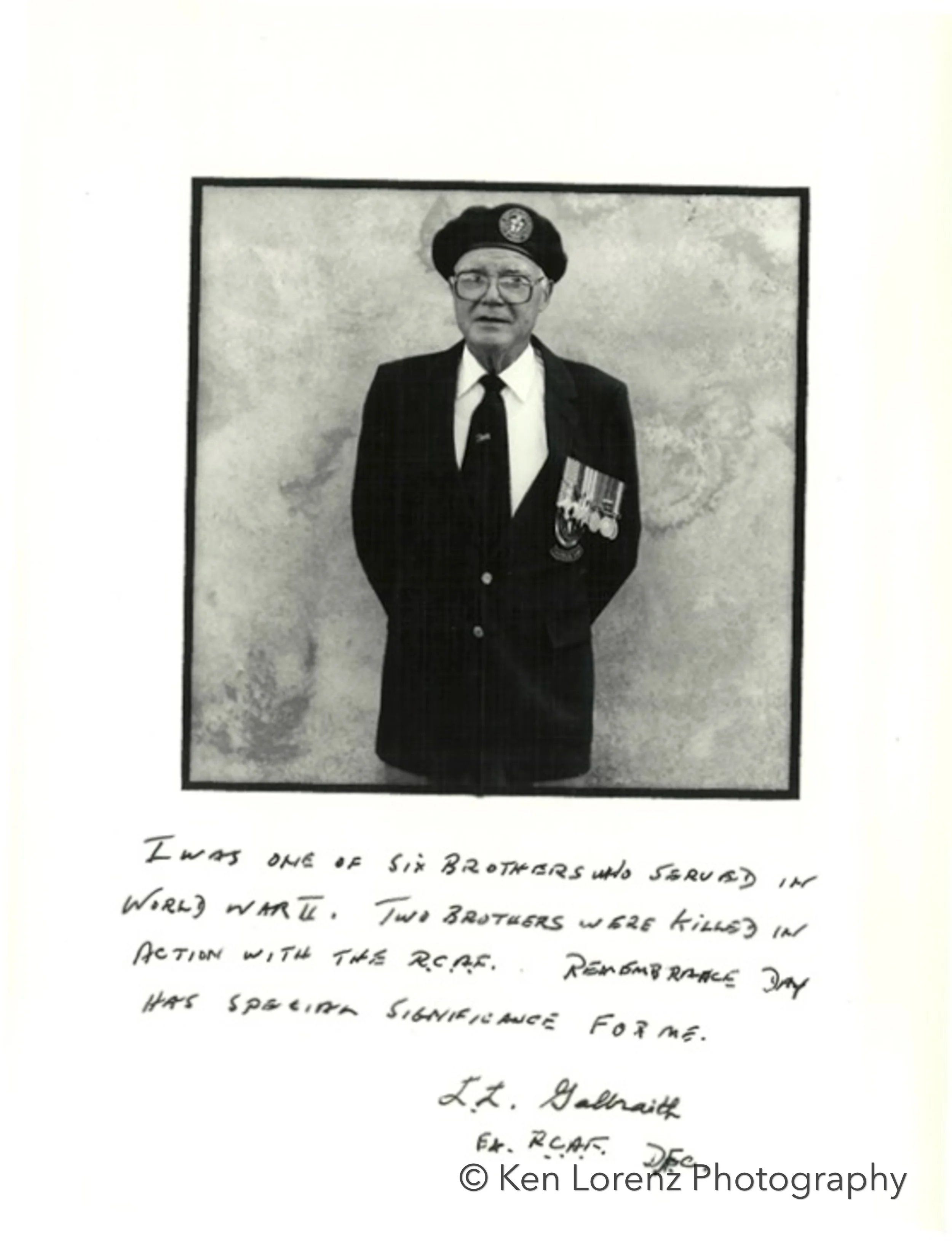

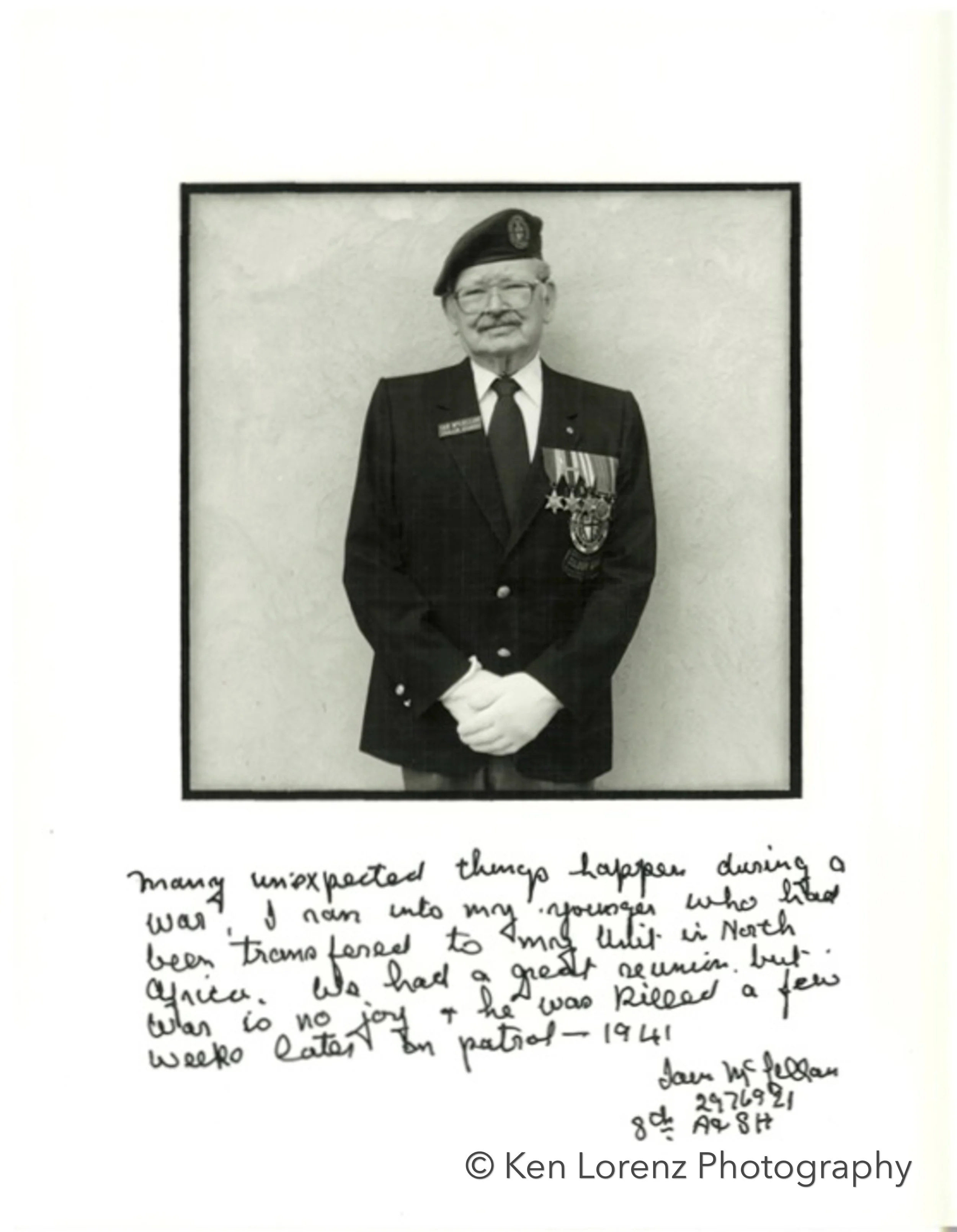

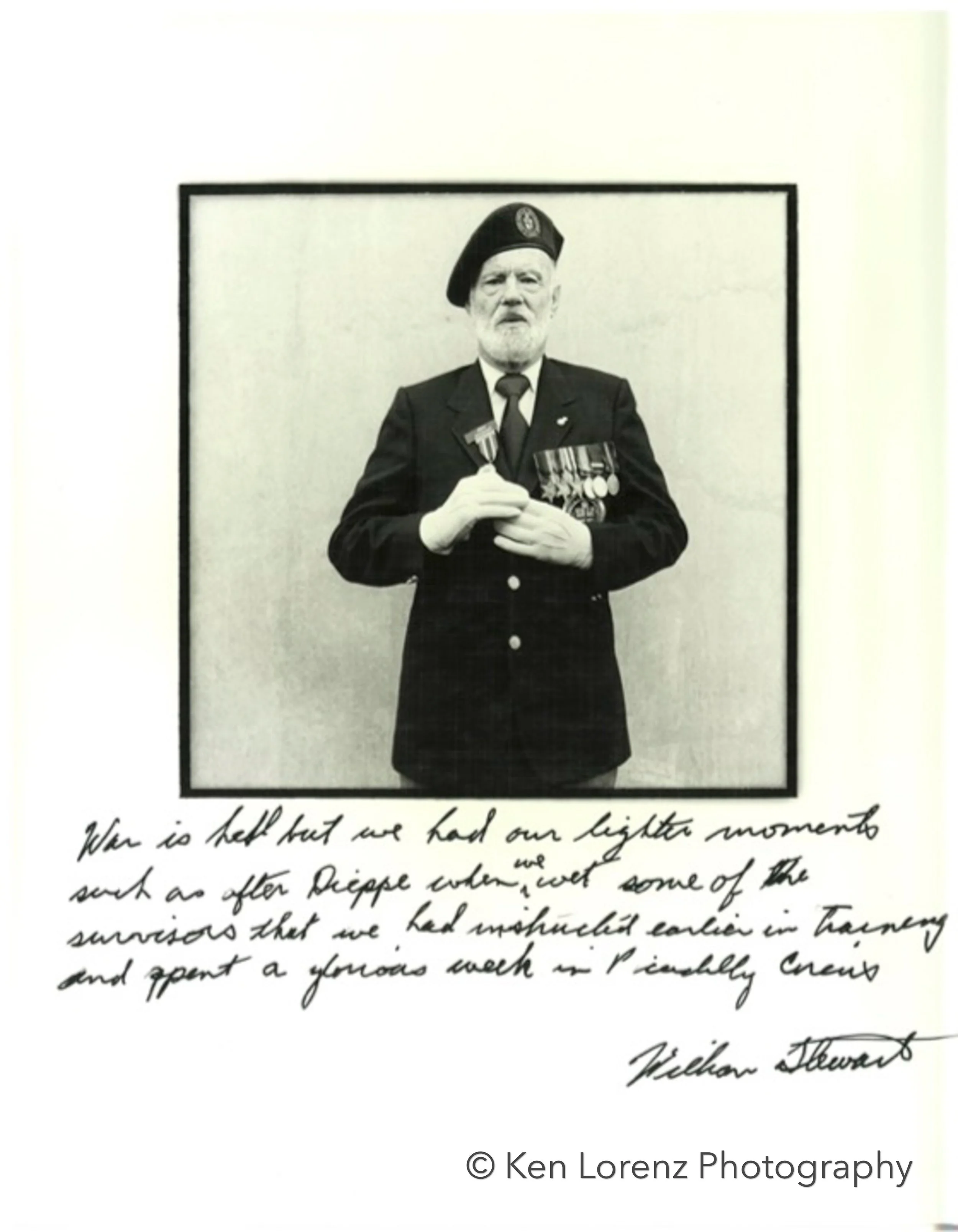

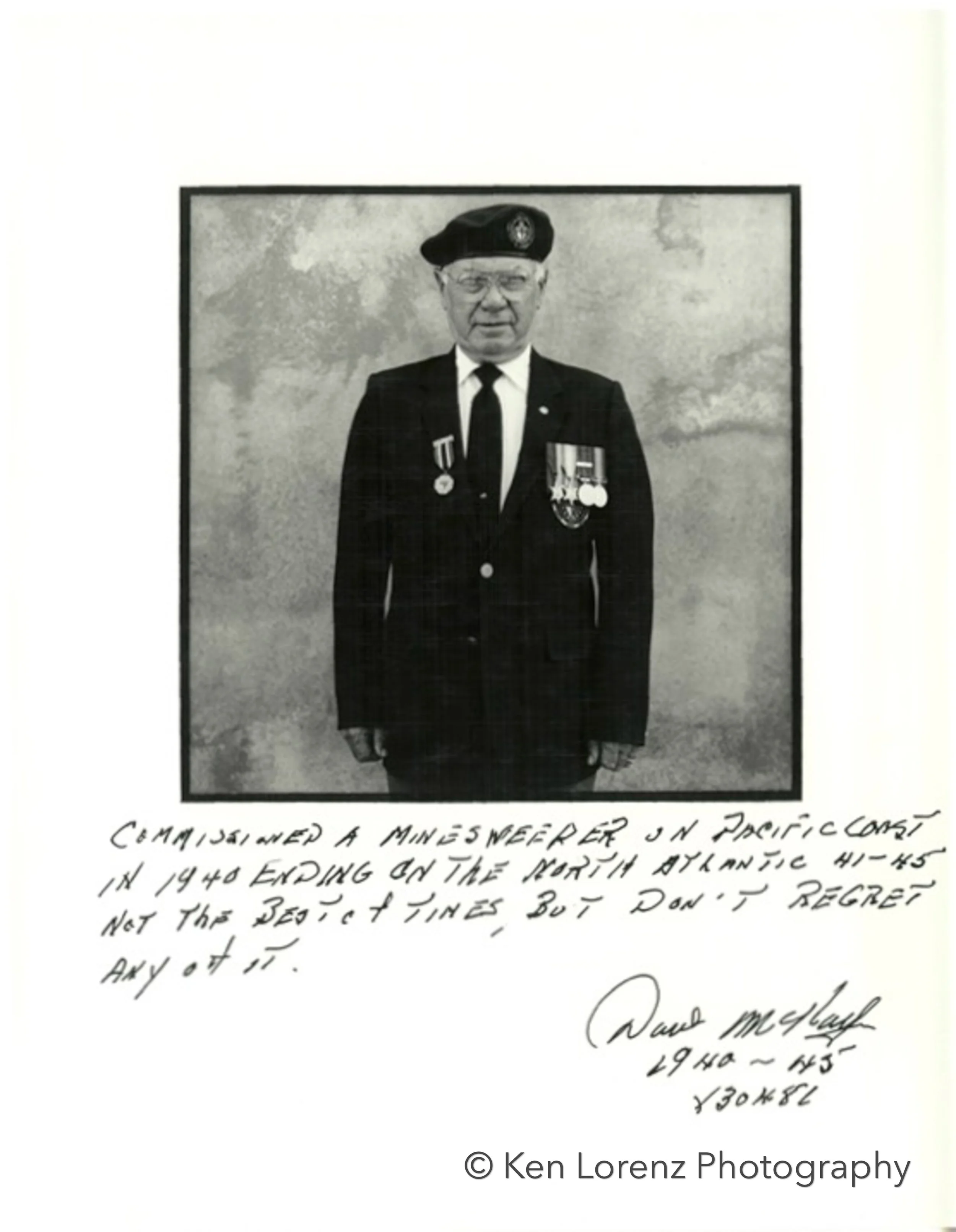

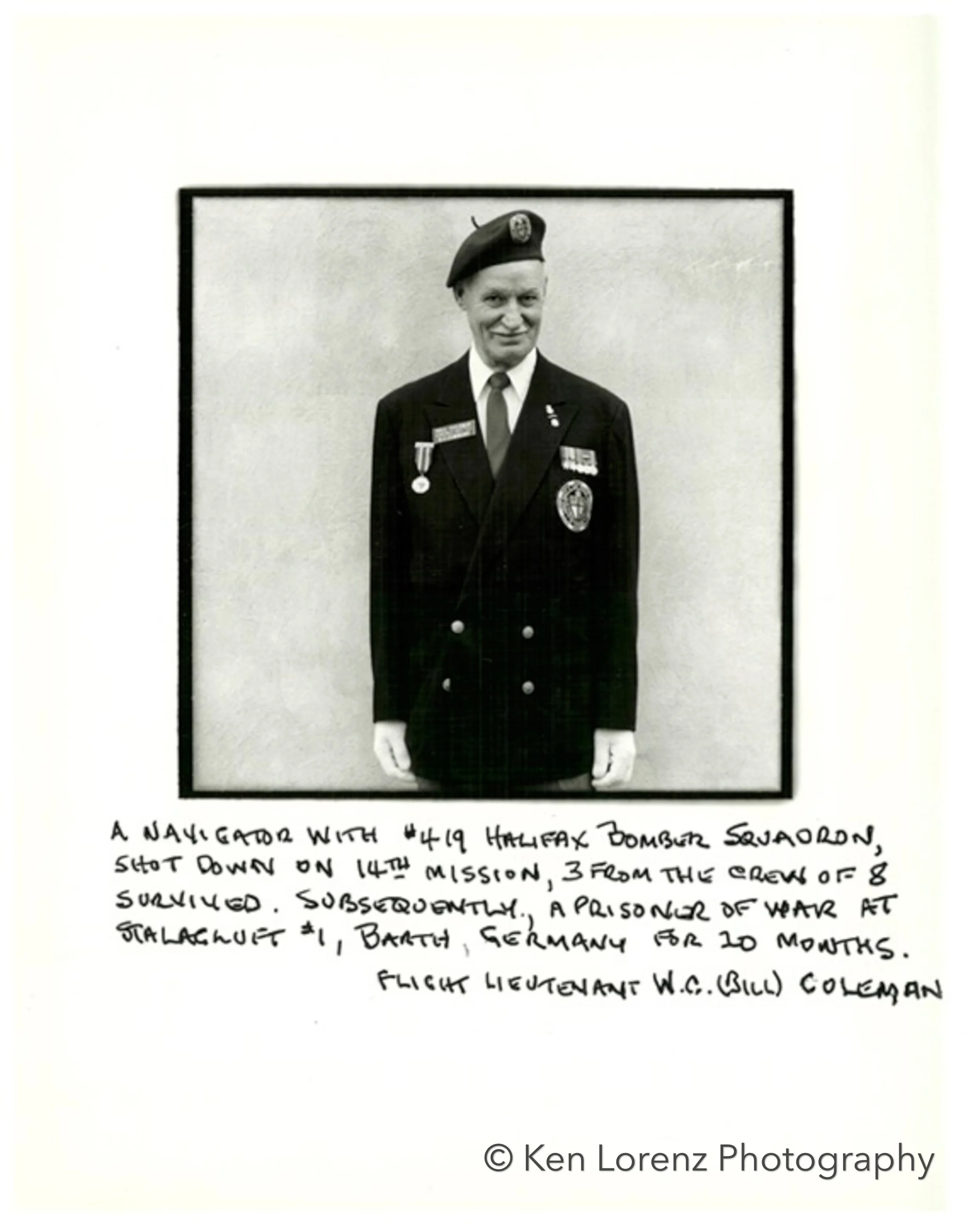

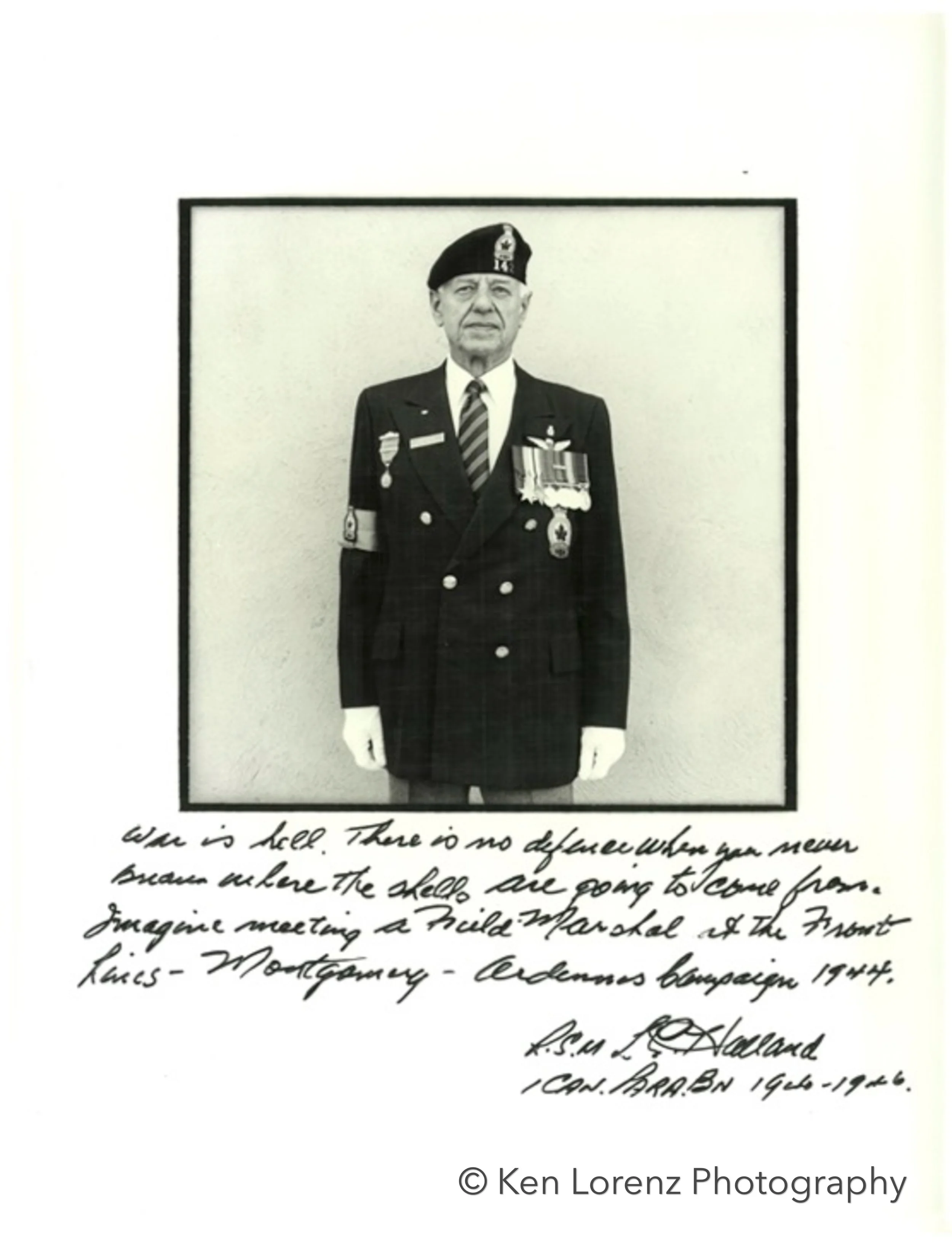

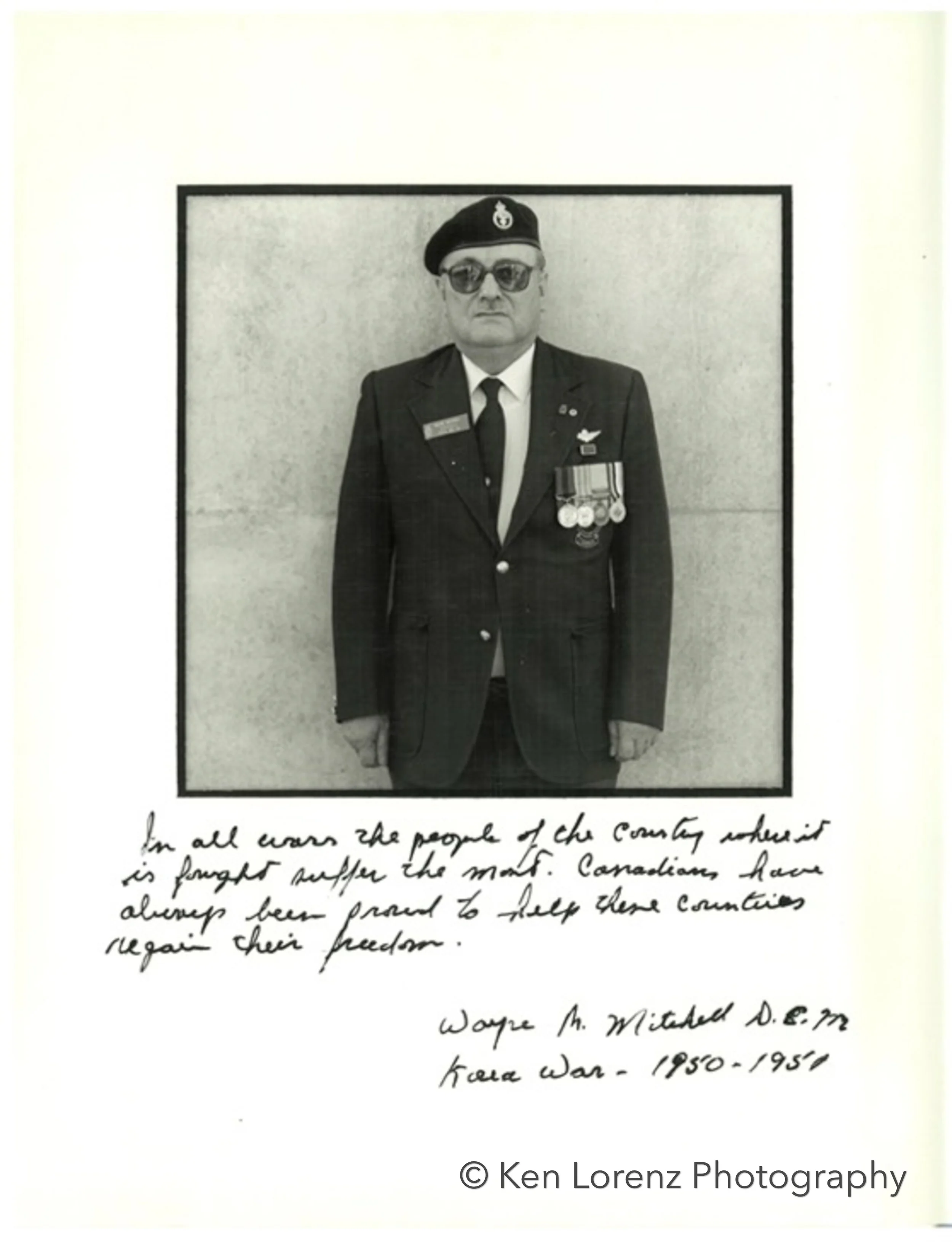

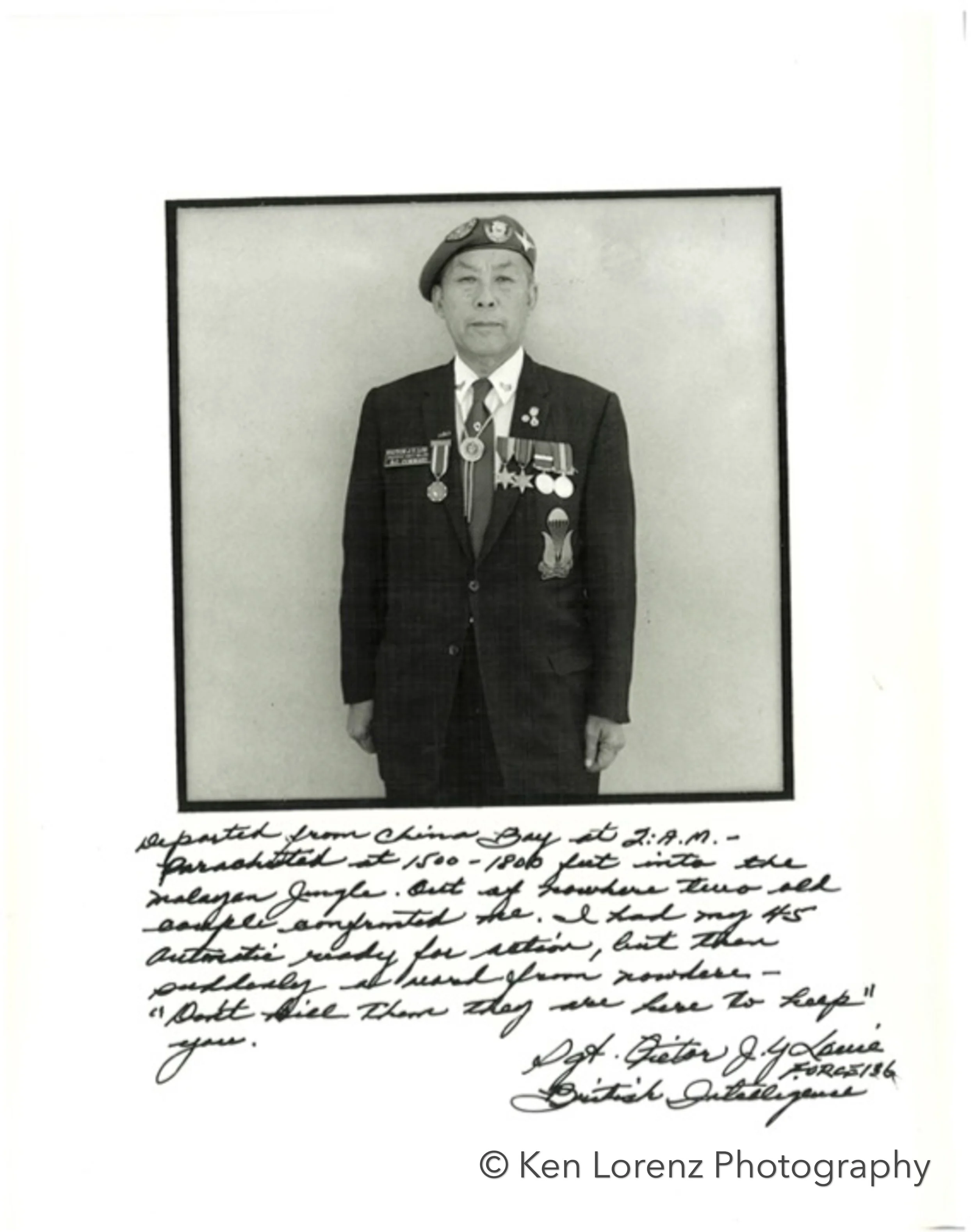

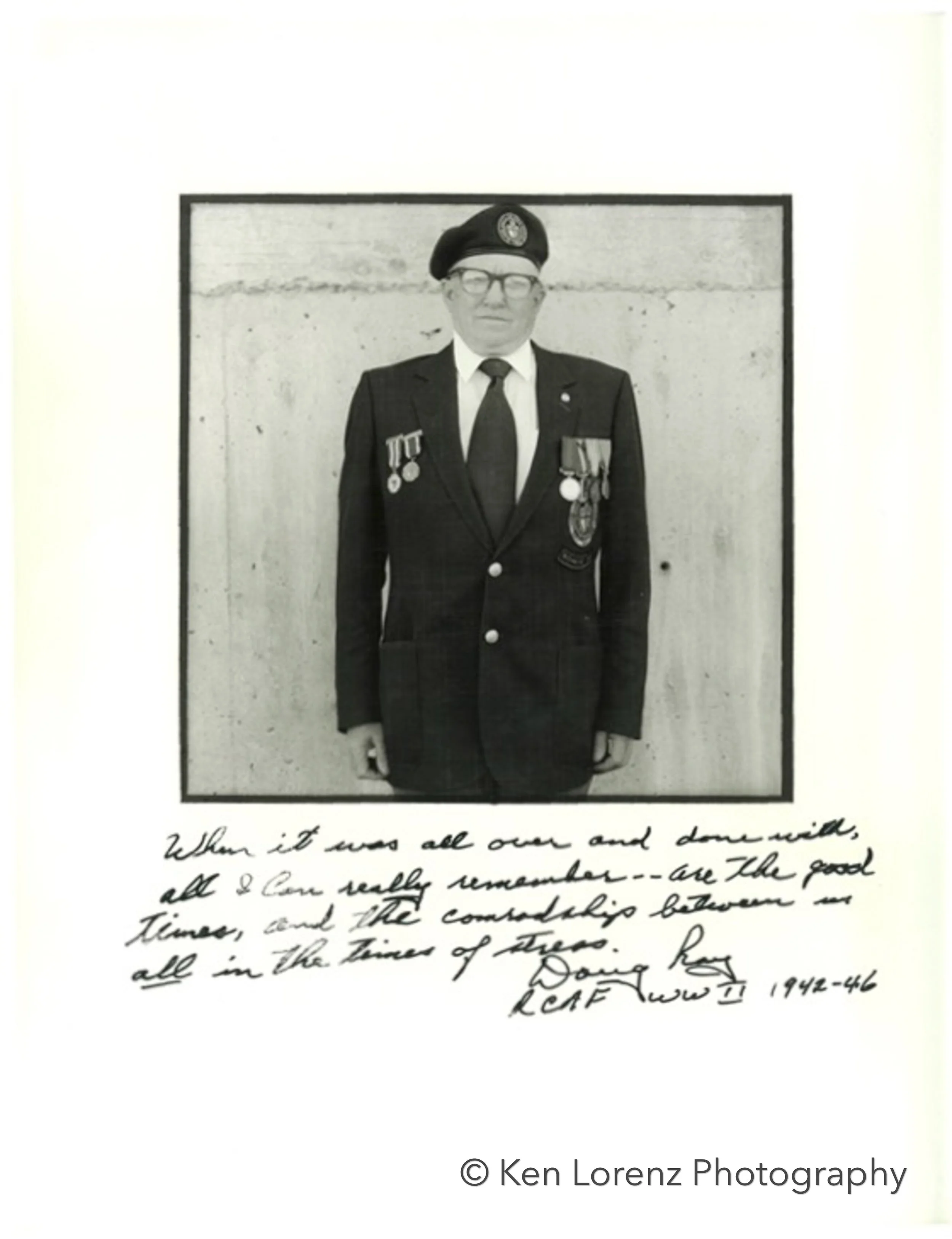

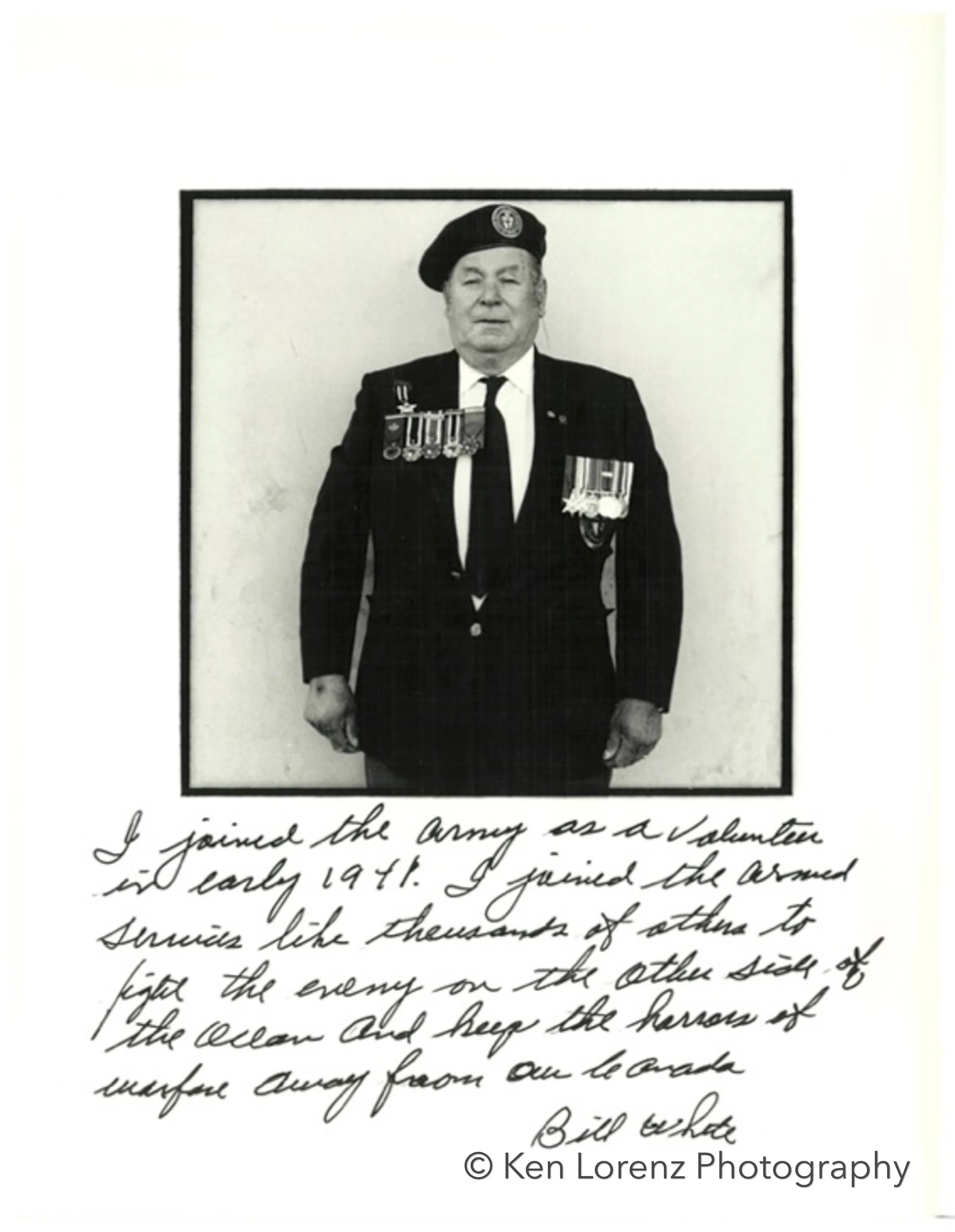

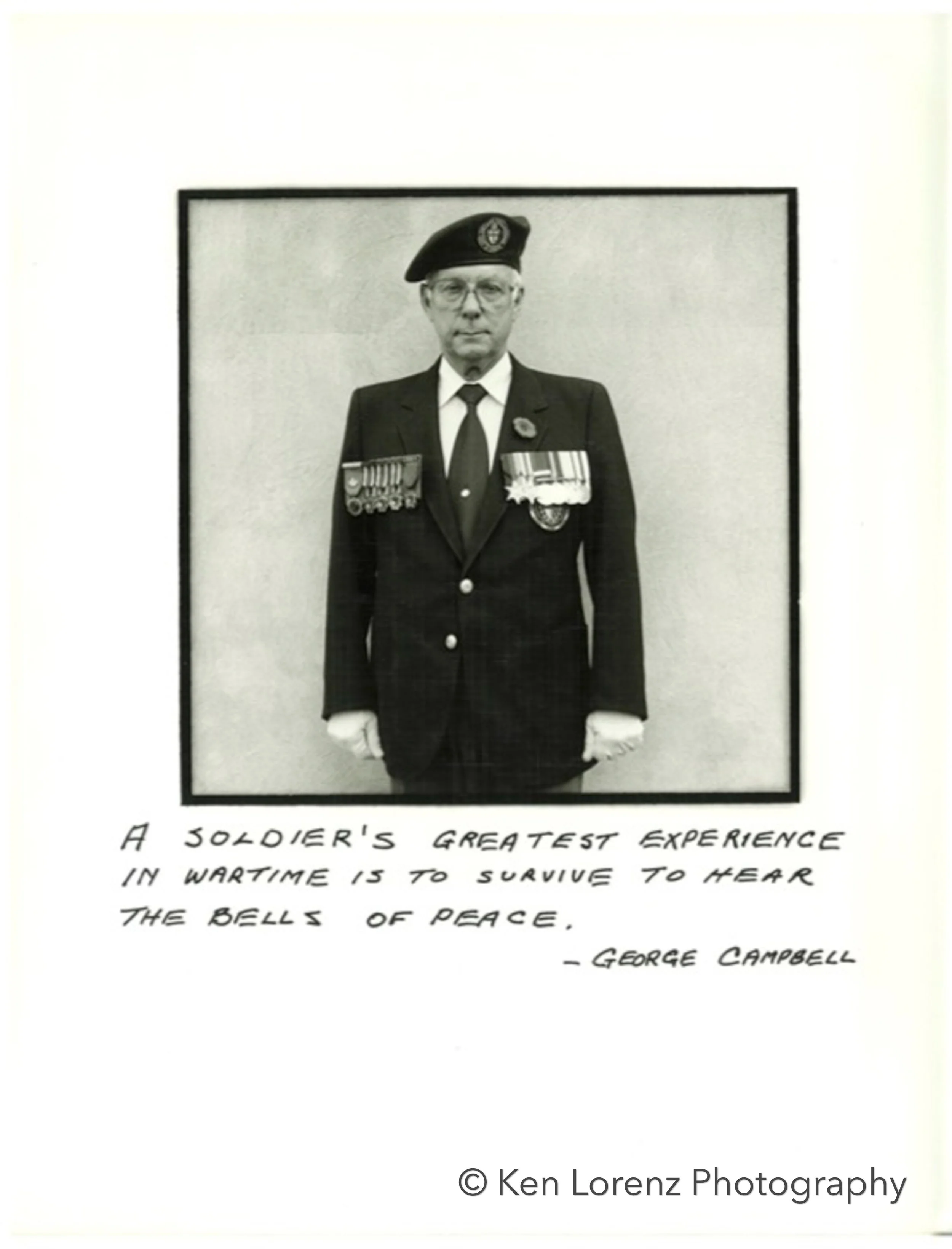

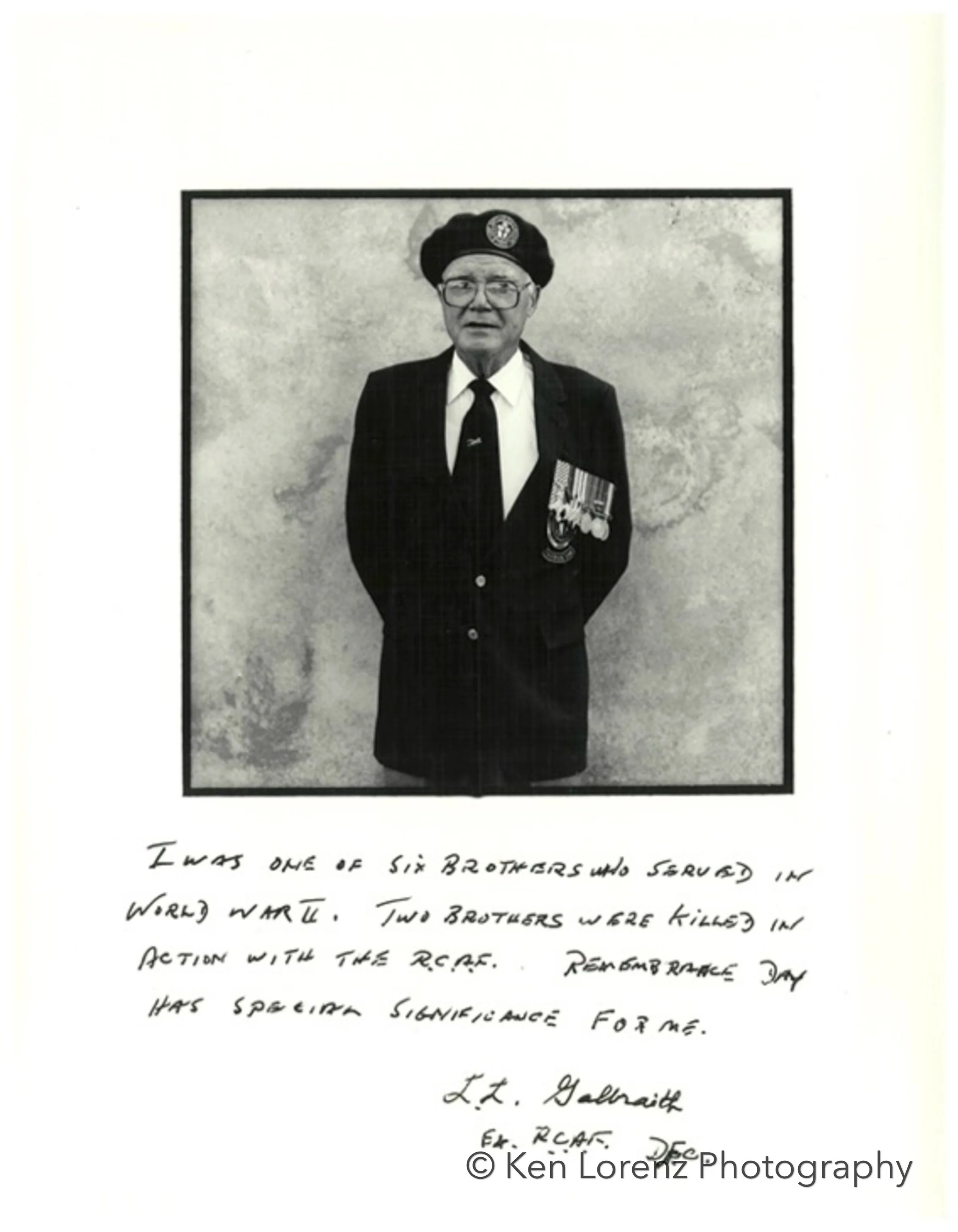

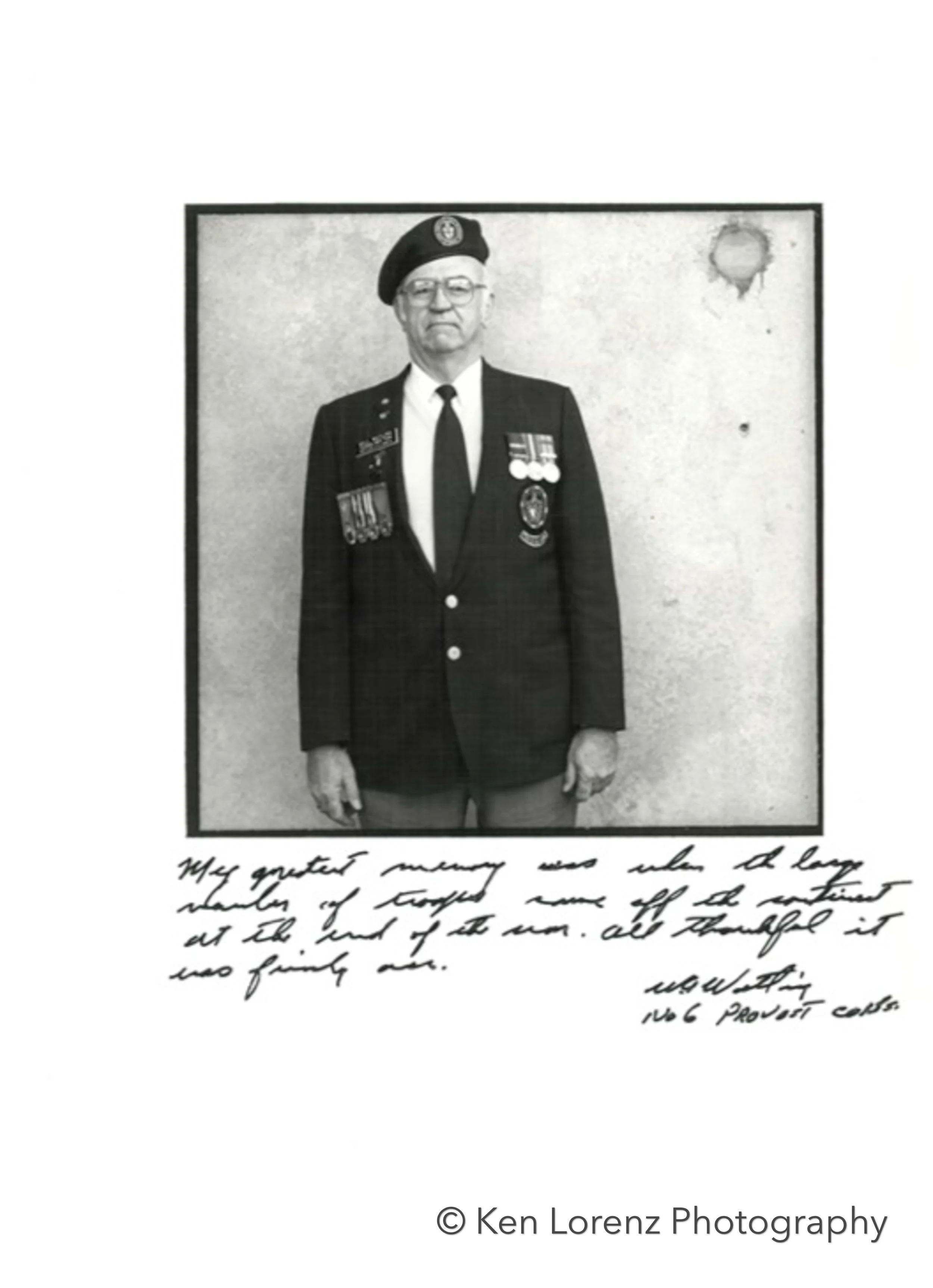

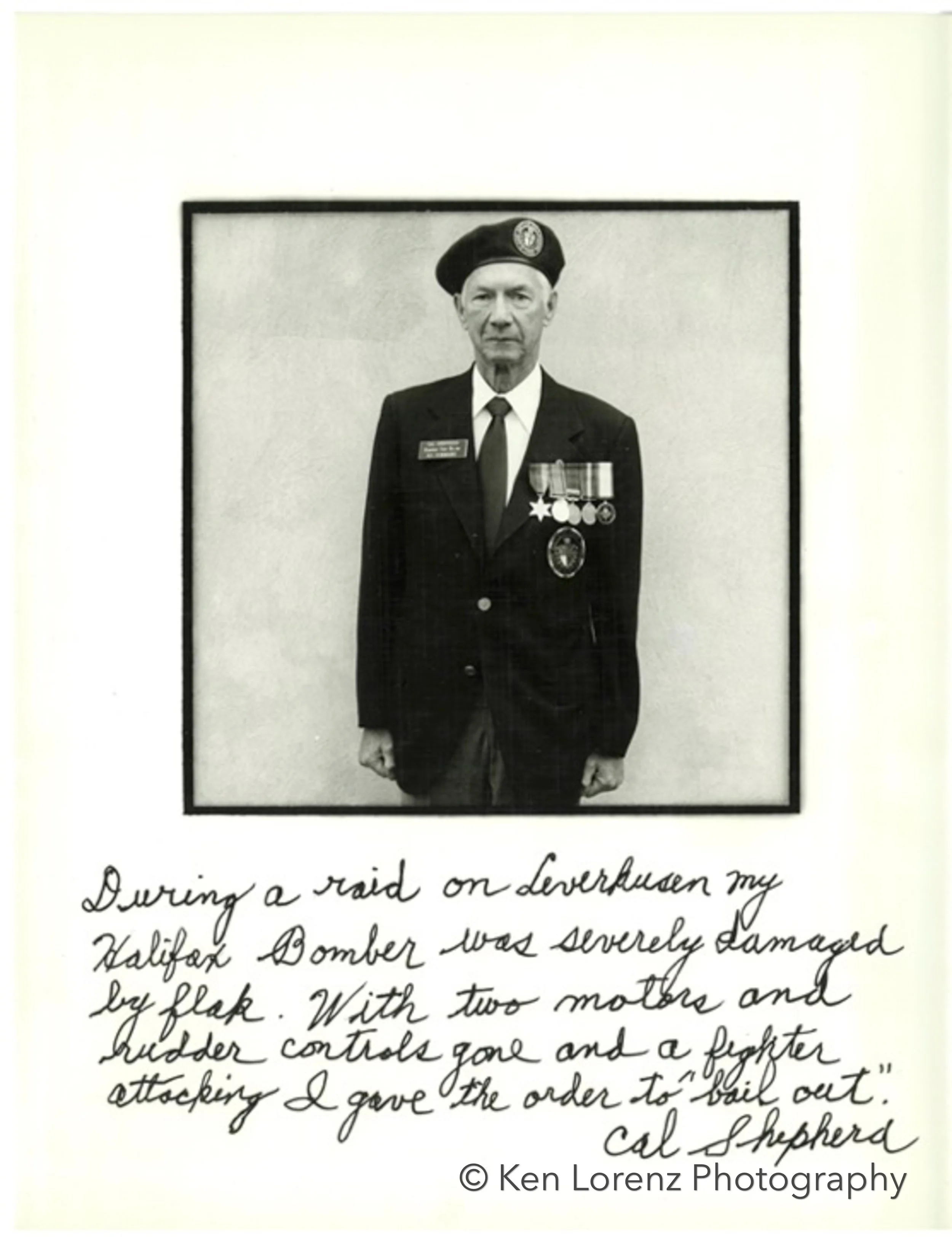

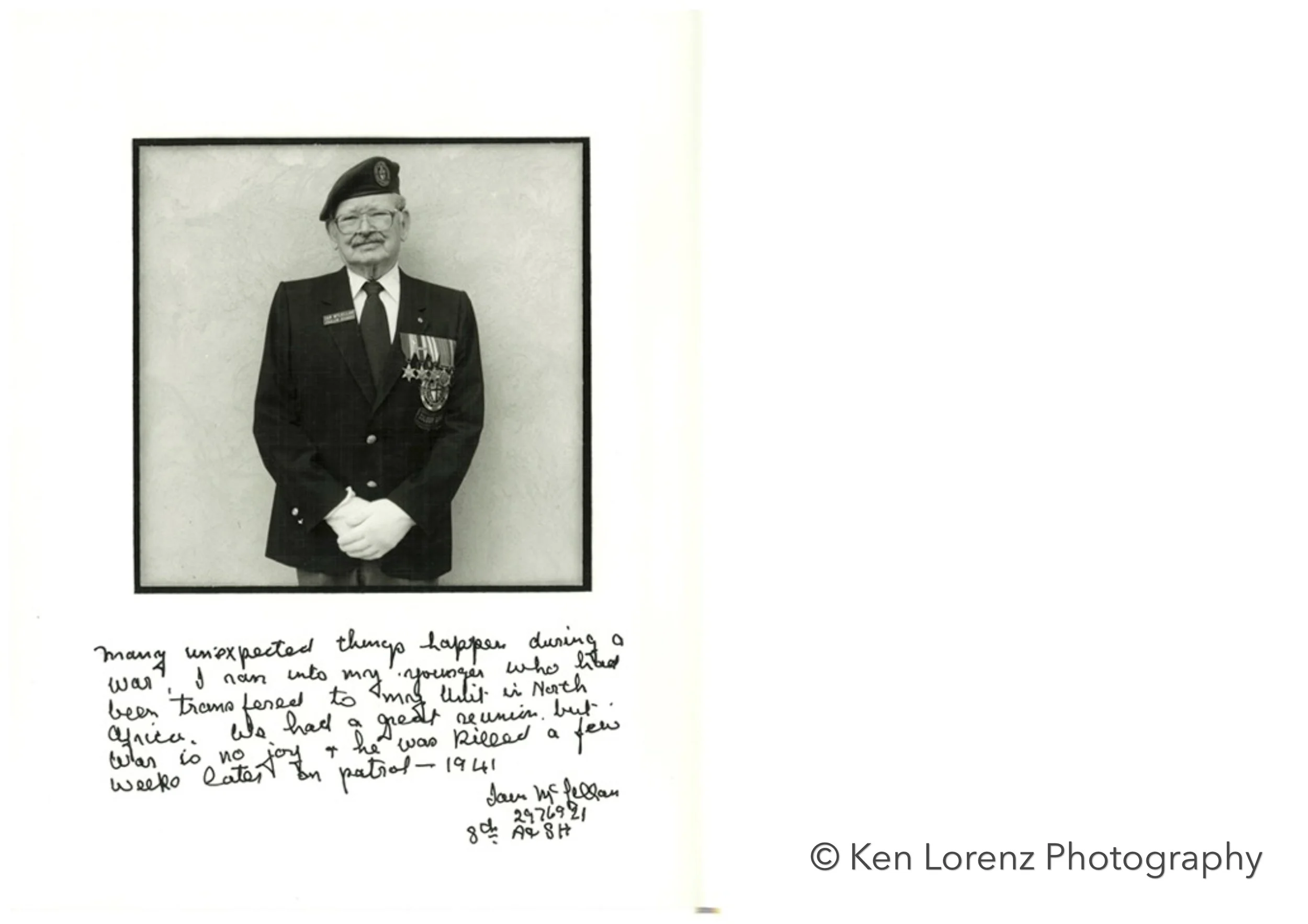

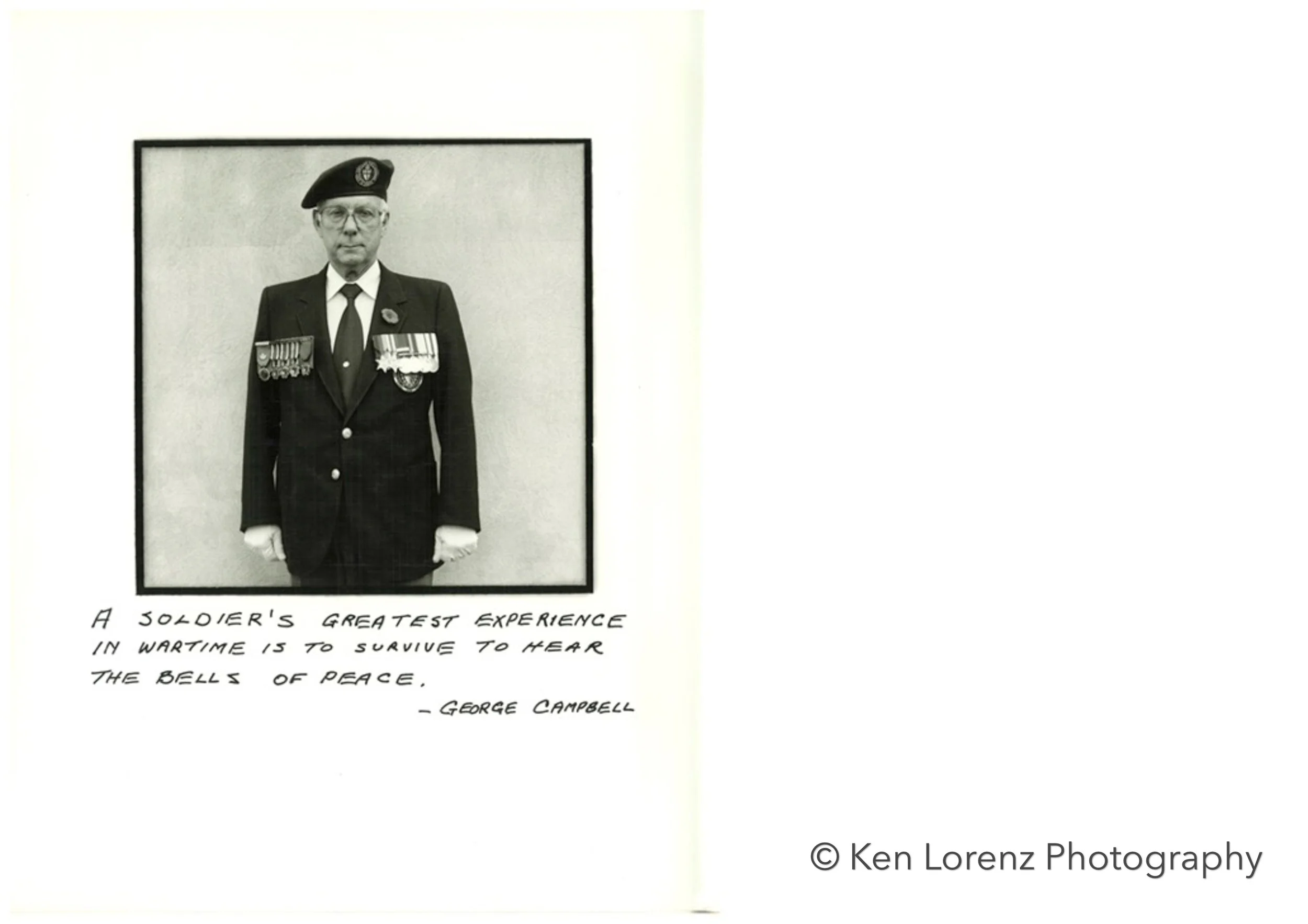

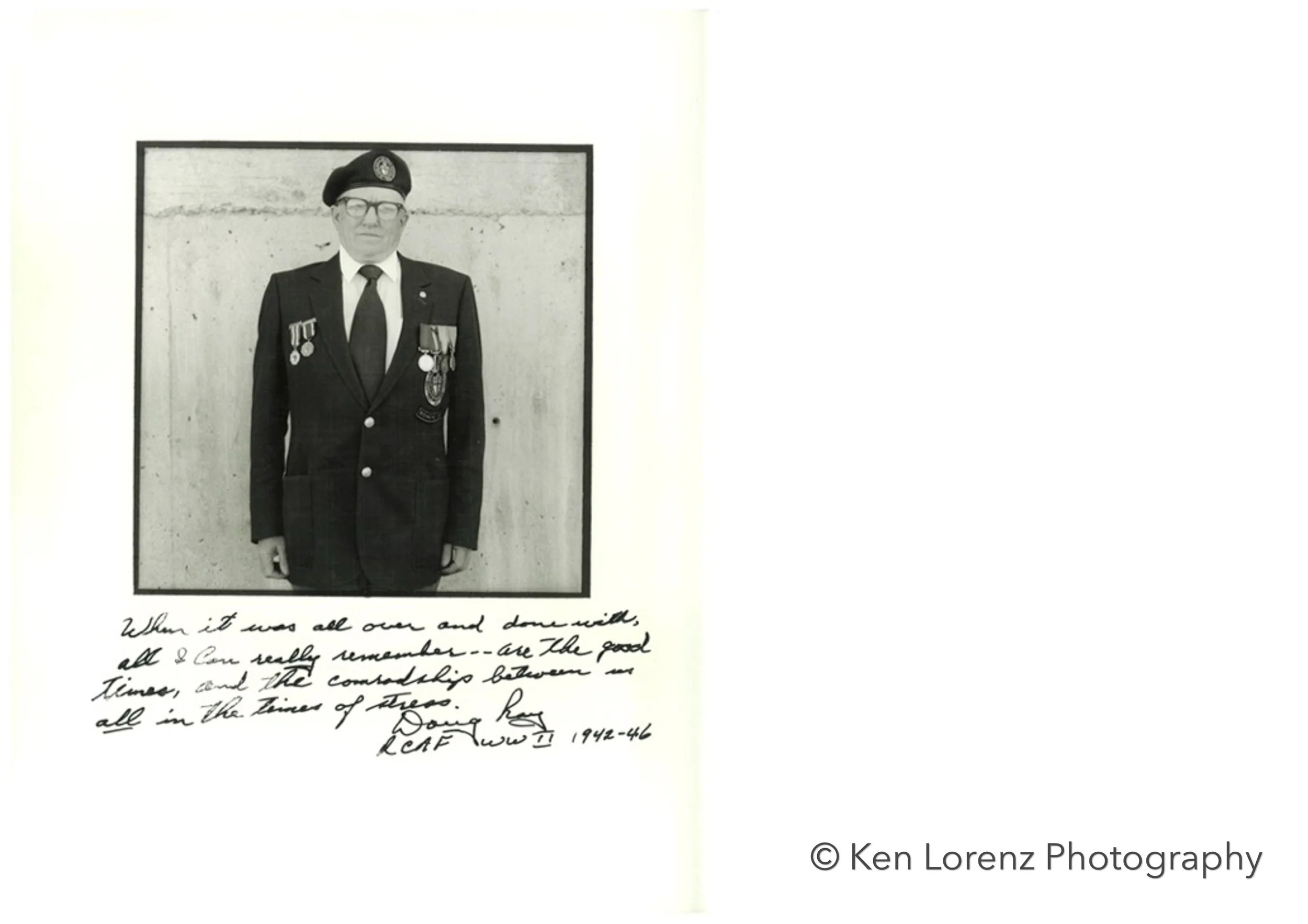

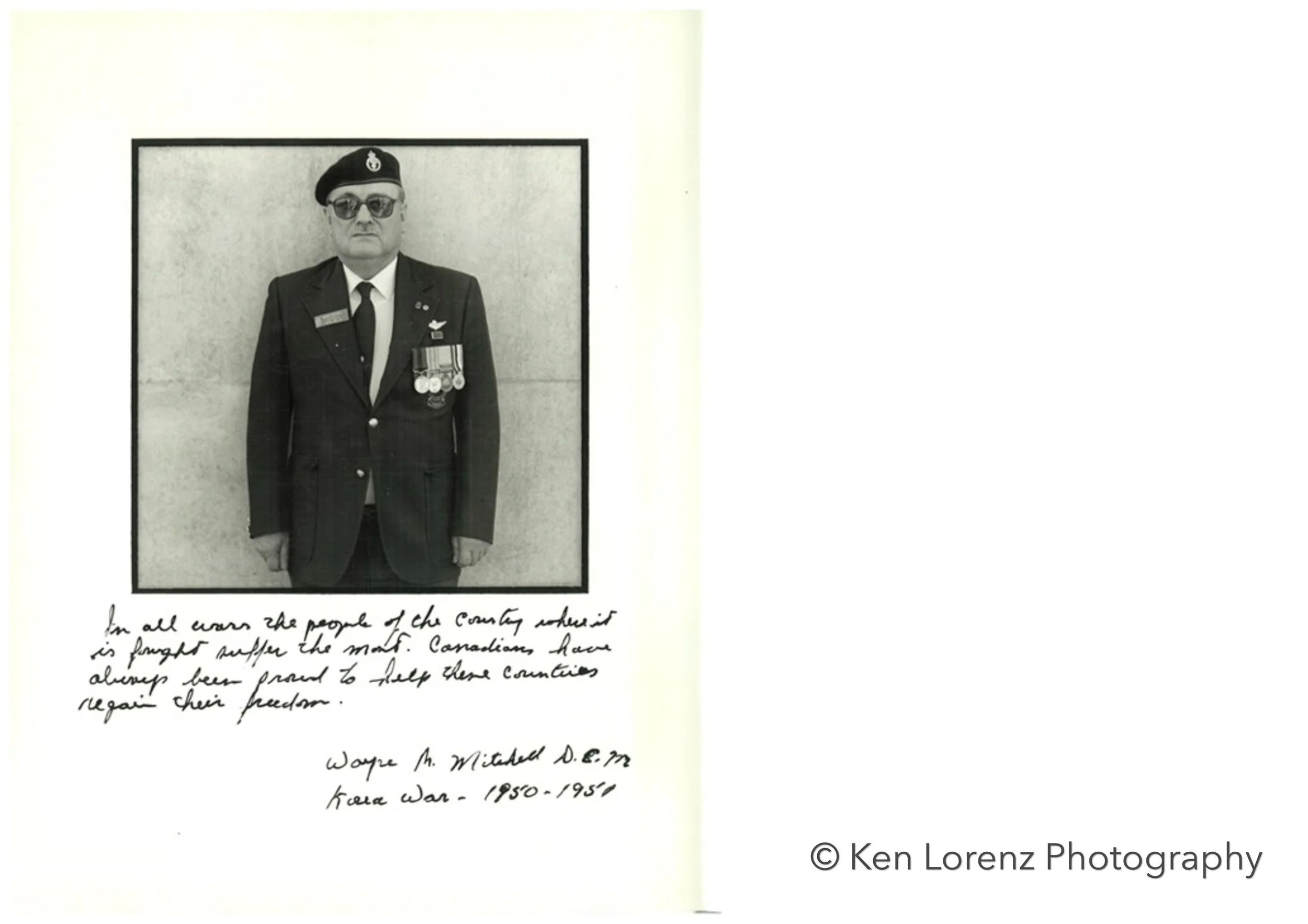

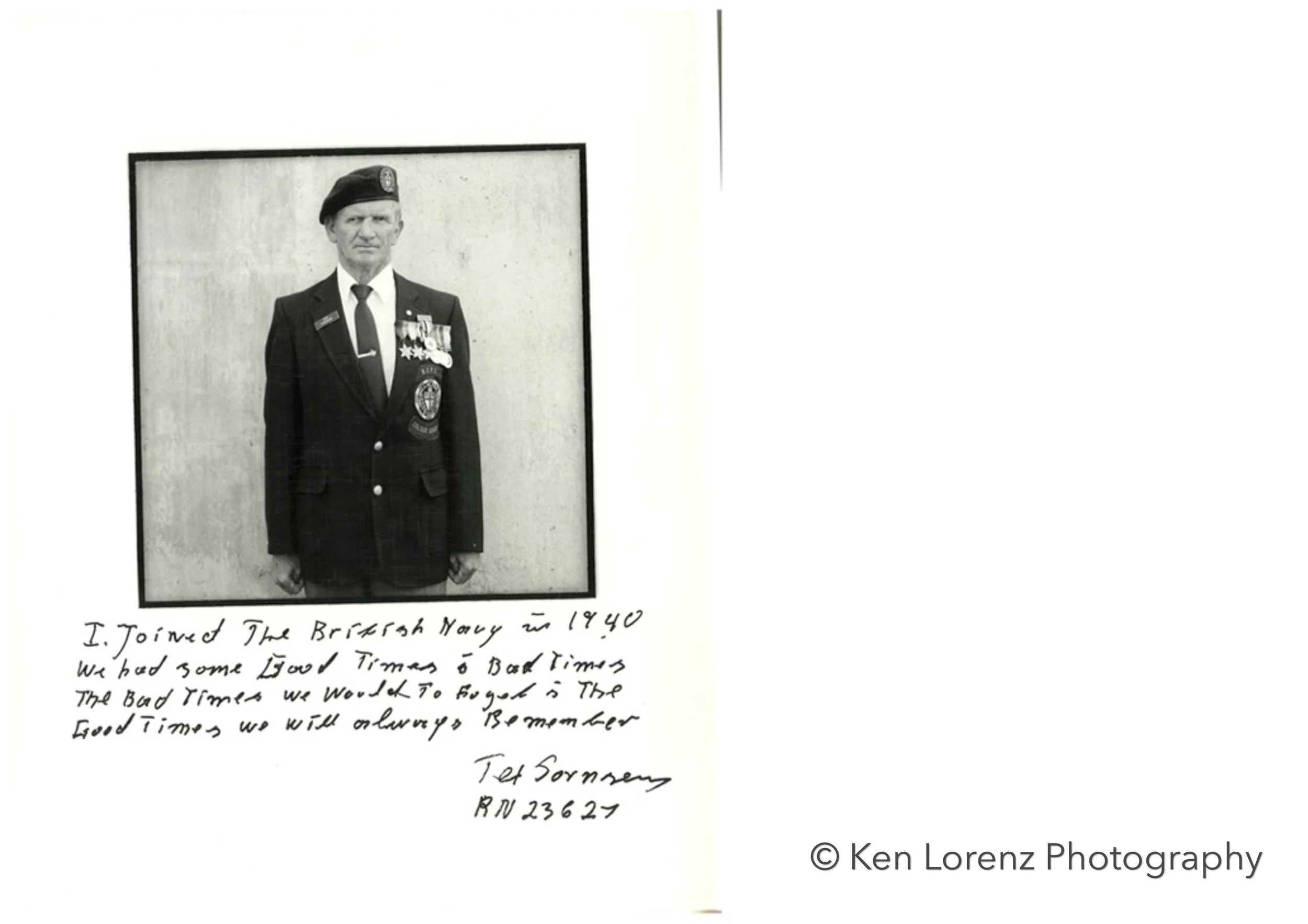

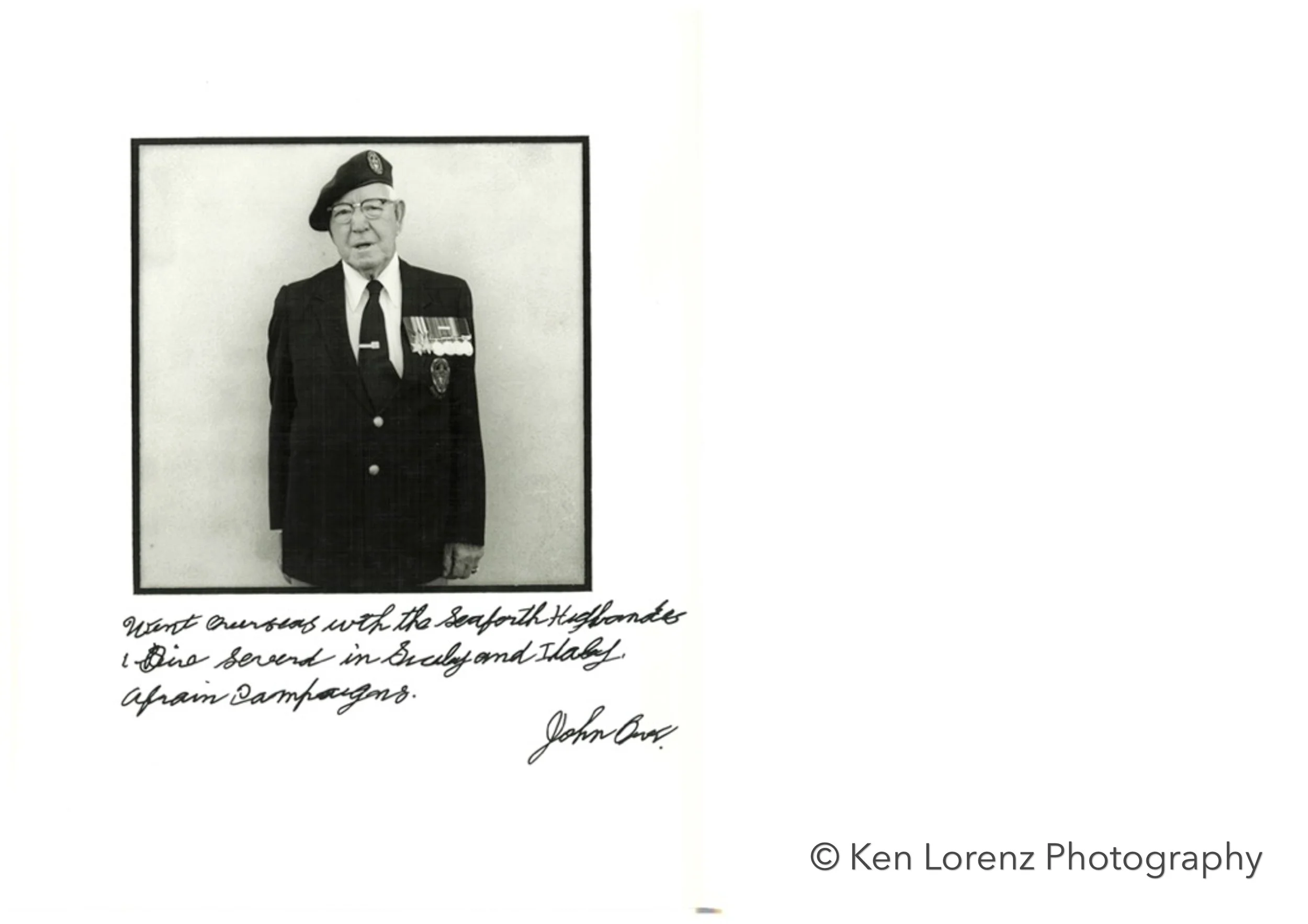

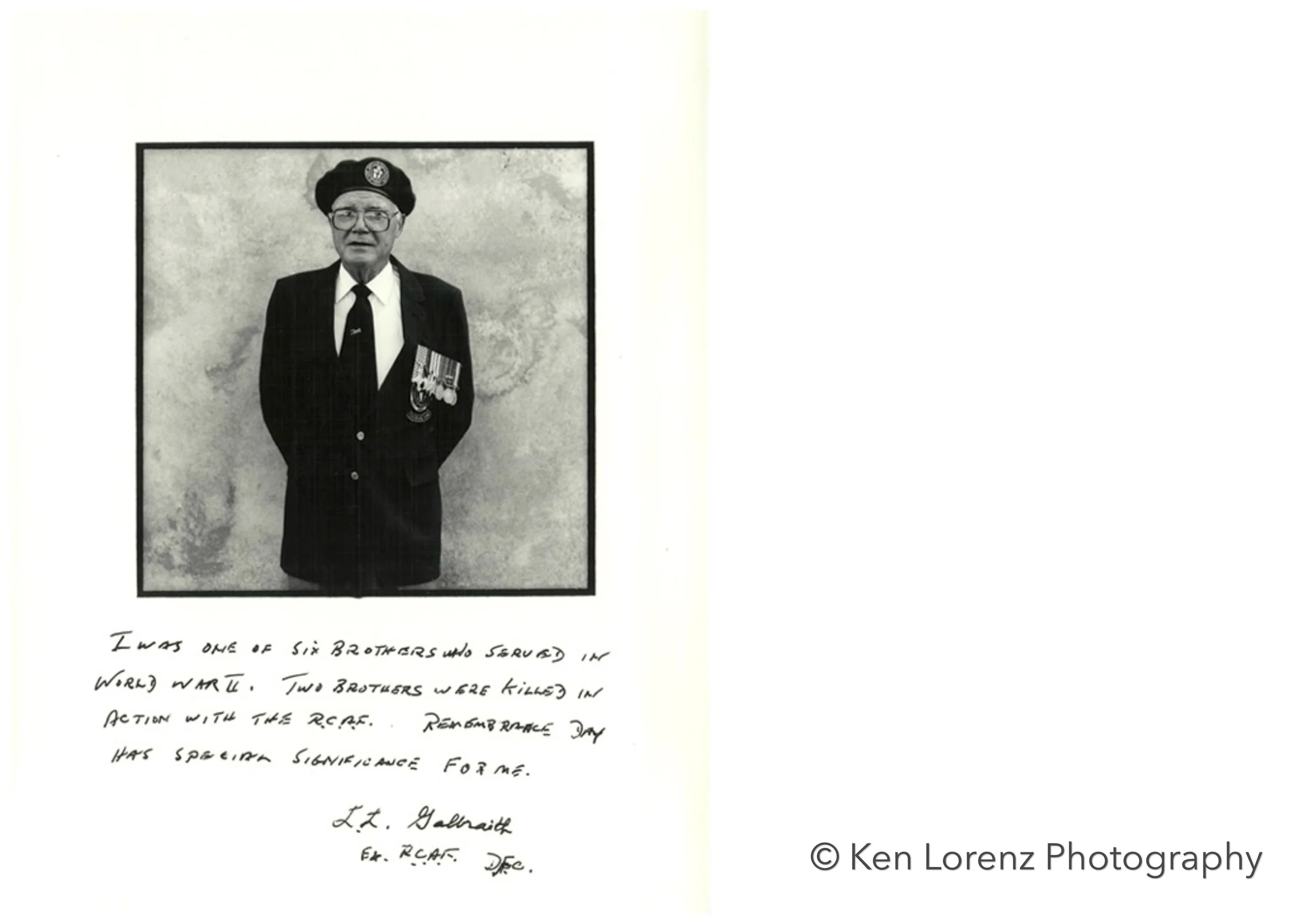

40 MEMOIRS; CANADIAN VETERANS RECALL WAR EXPERIENCES

40 MEMOIRS; CANADIAN VETERANS RECALL WAR EXPERIENCES

Photographs by Ken Lorenz Written by Kenneth Meiklejohn

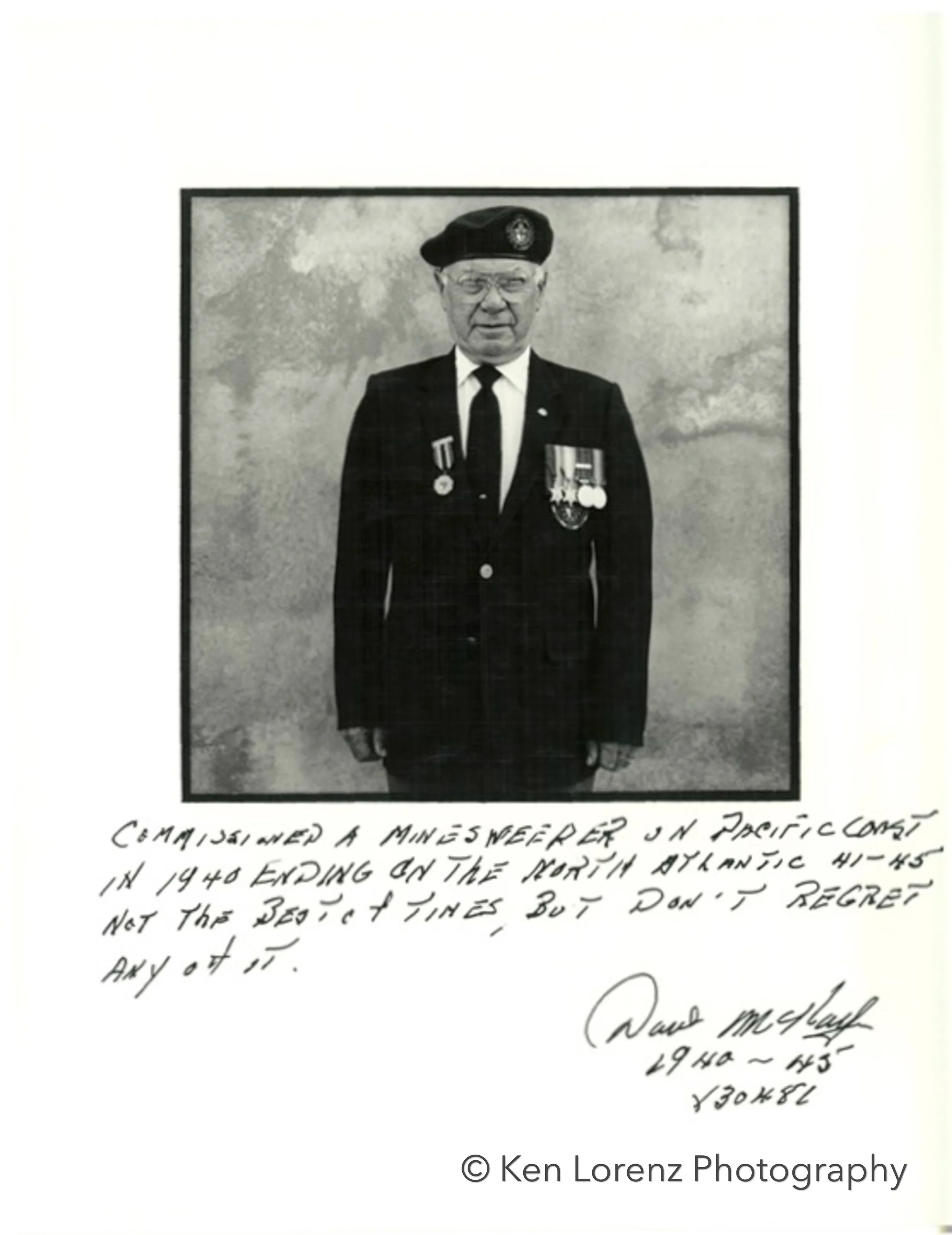

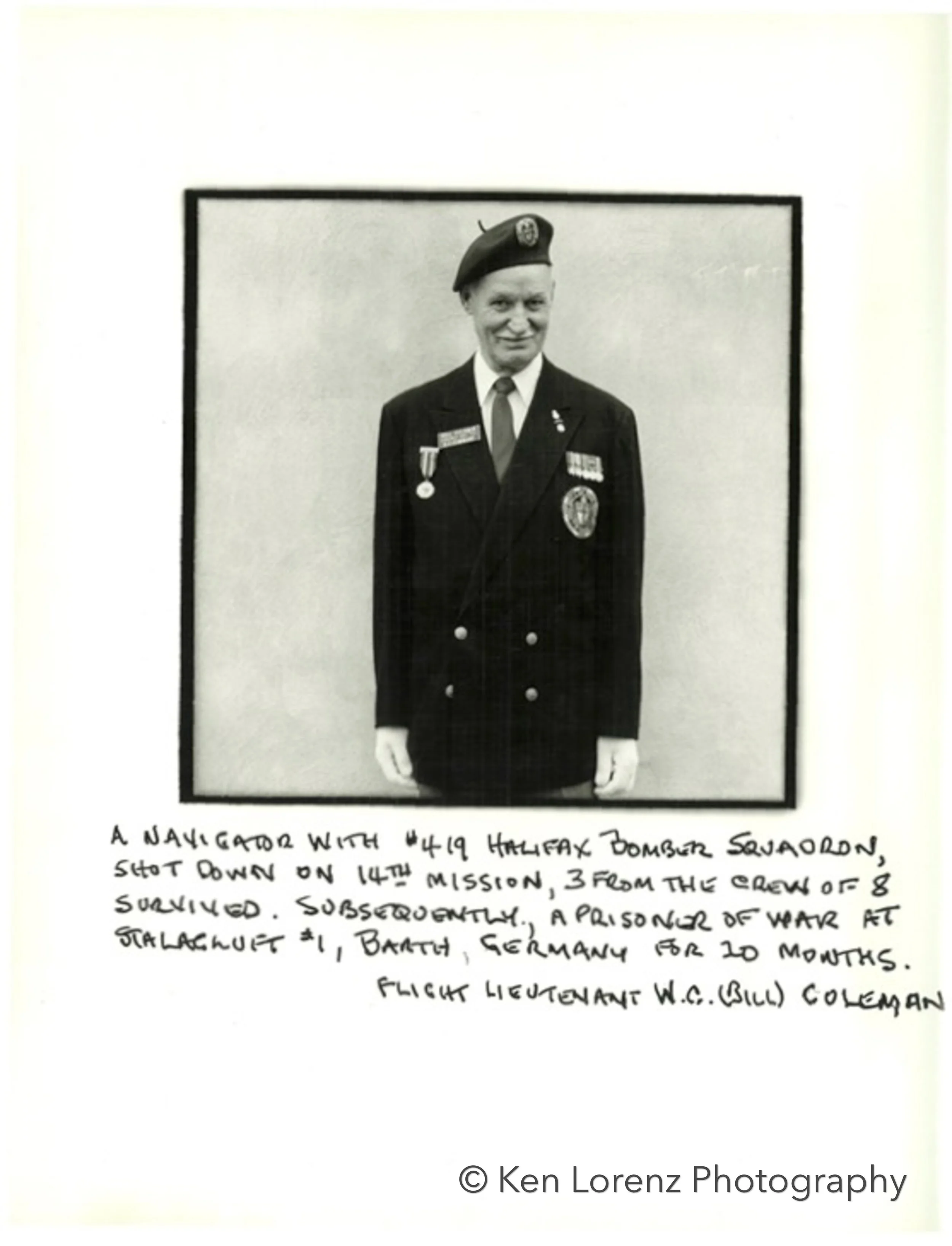

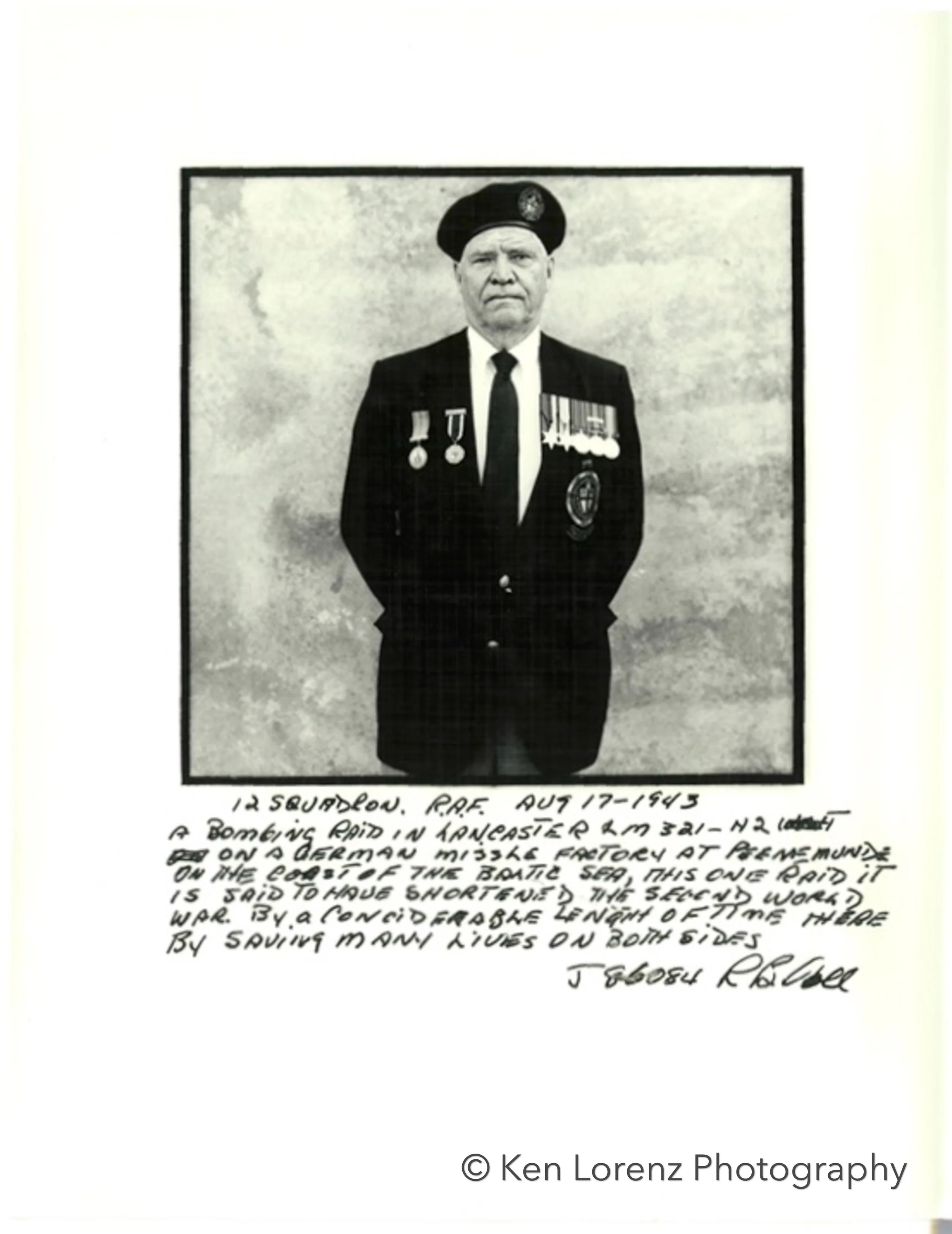

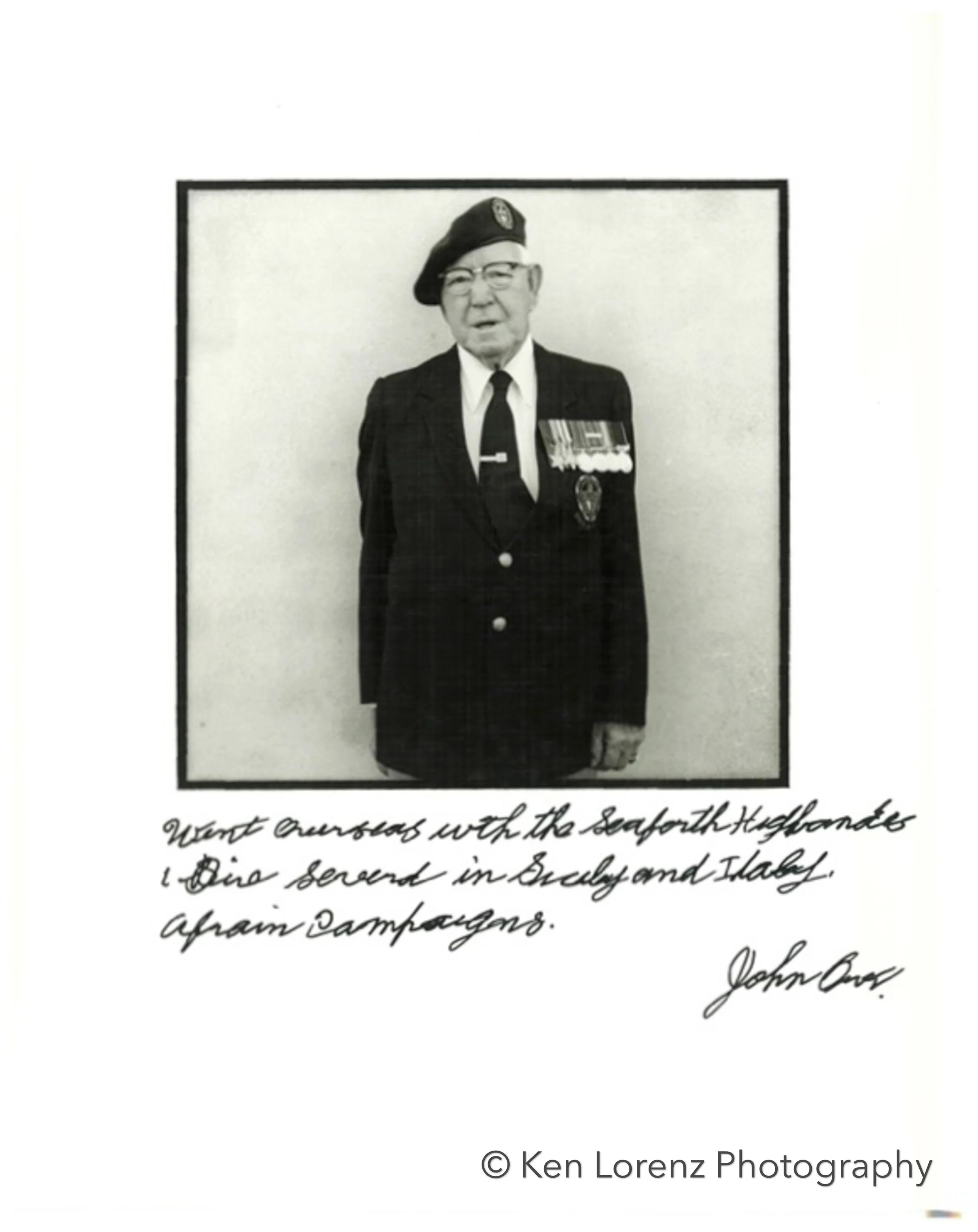

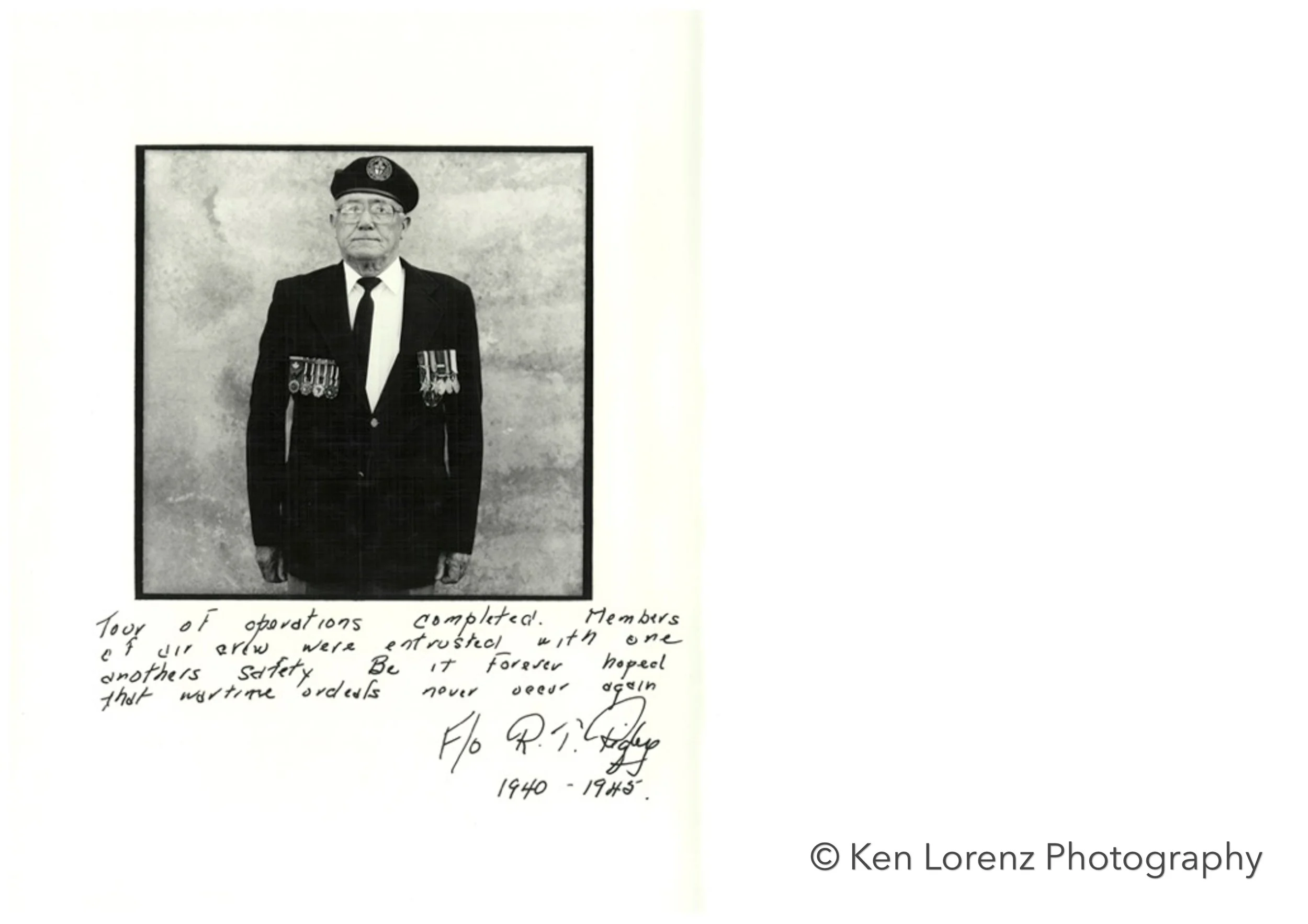

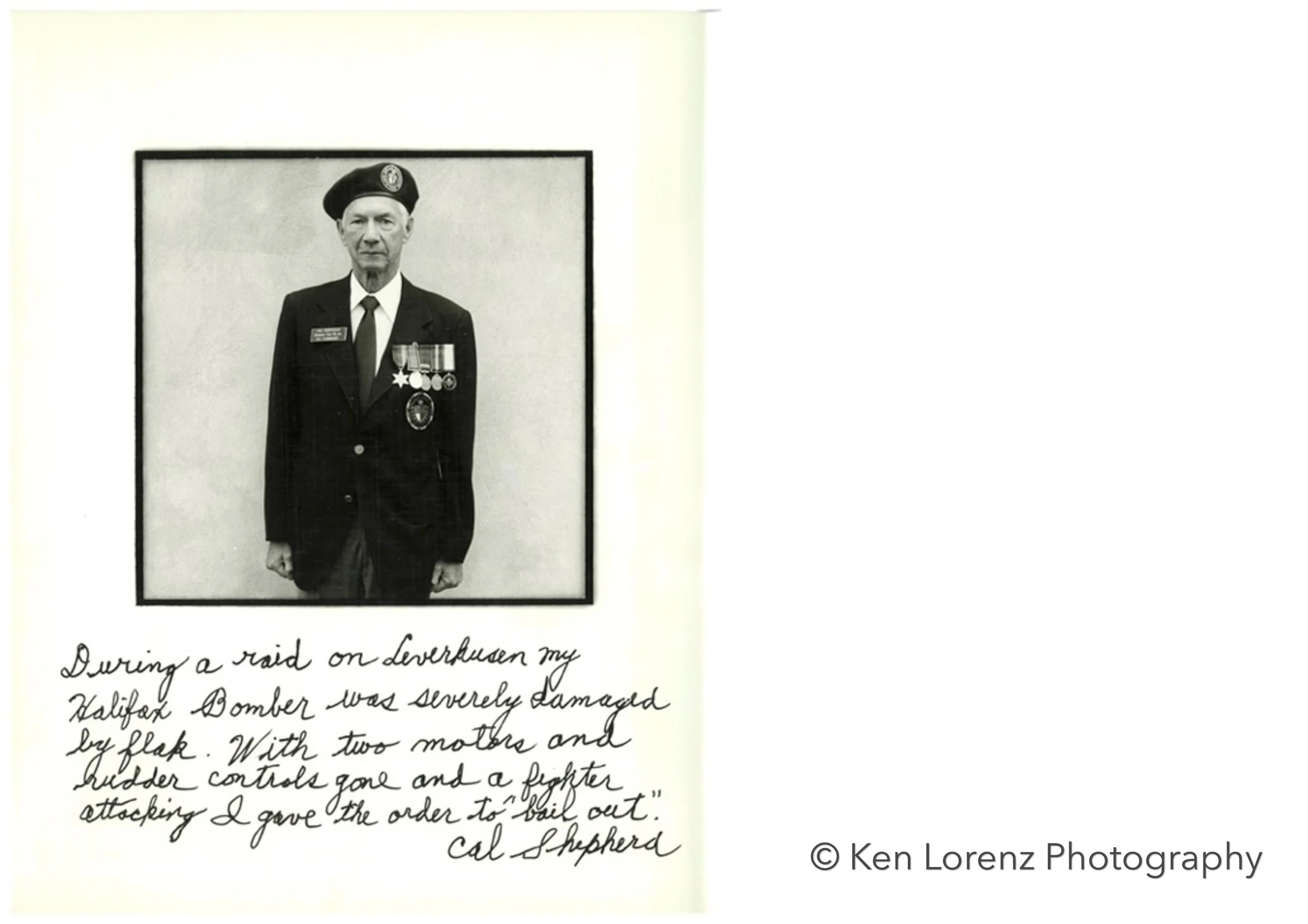

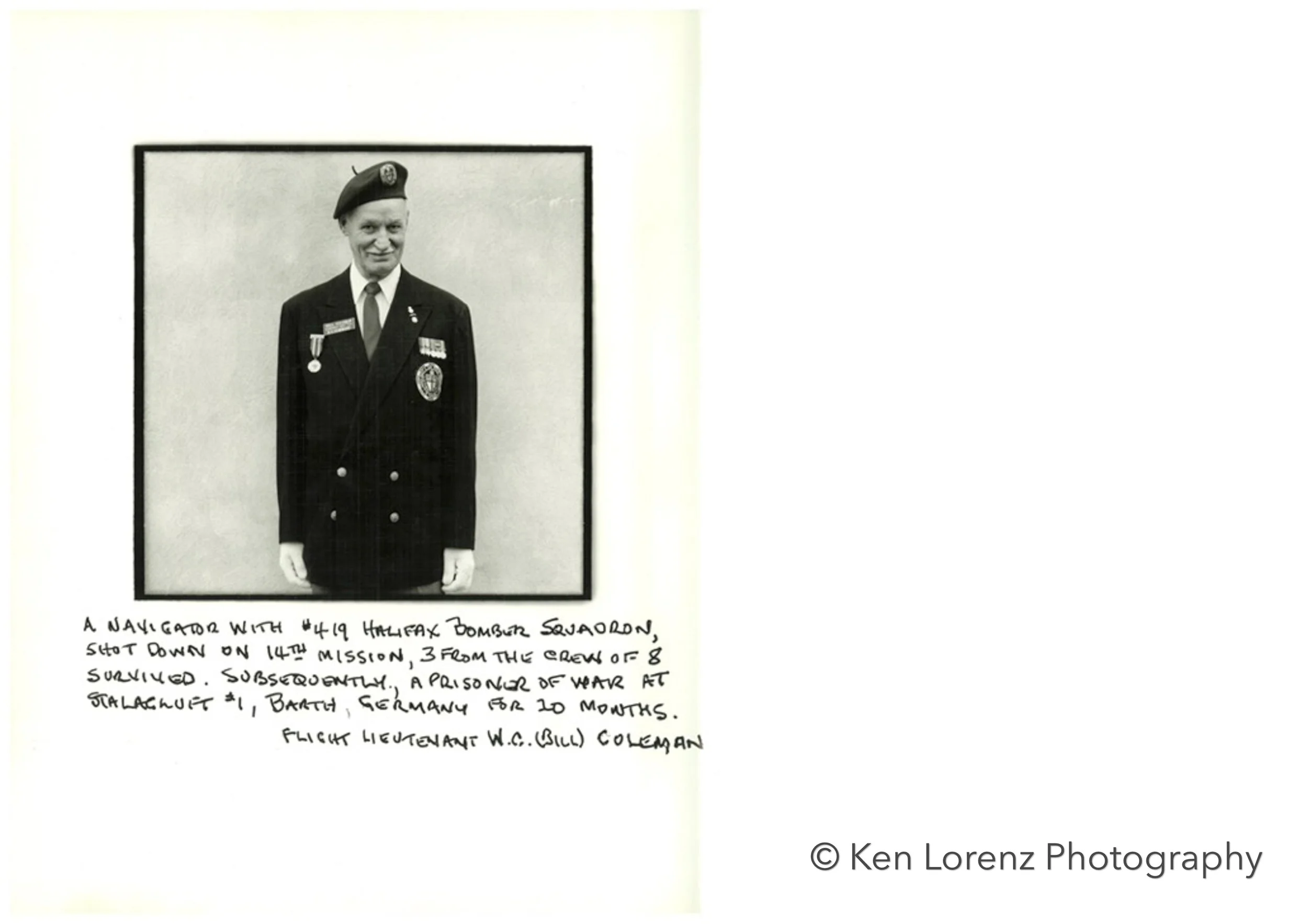

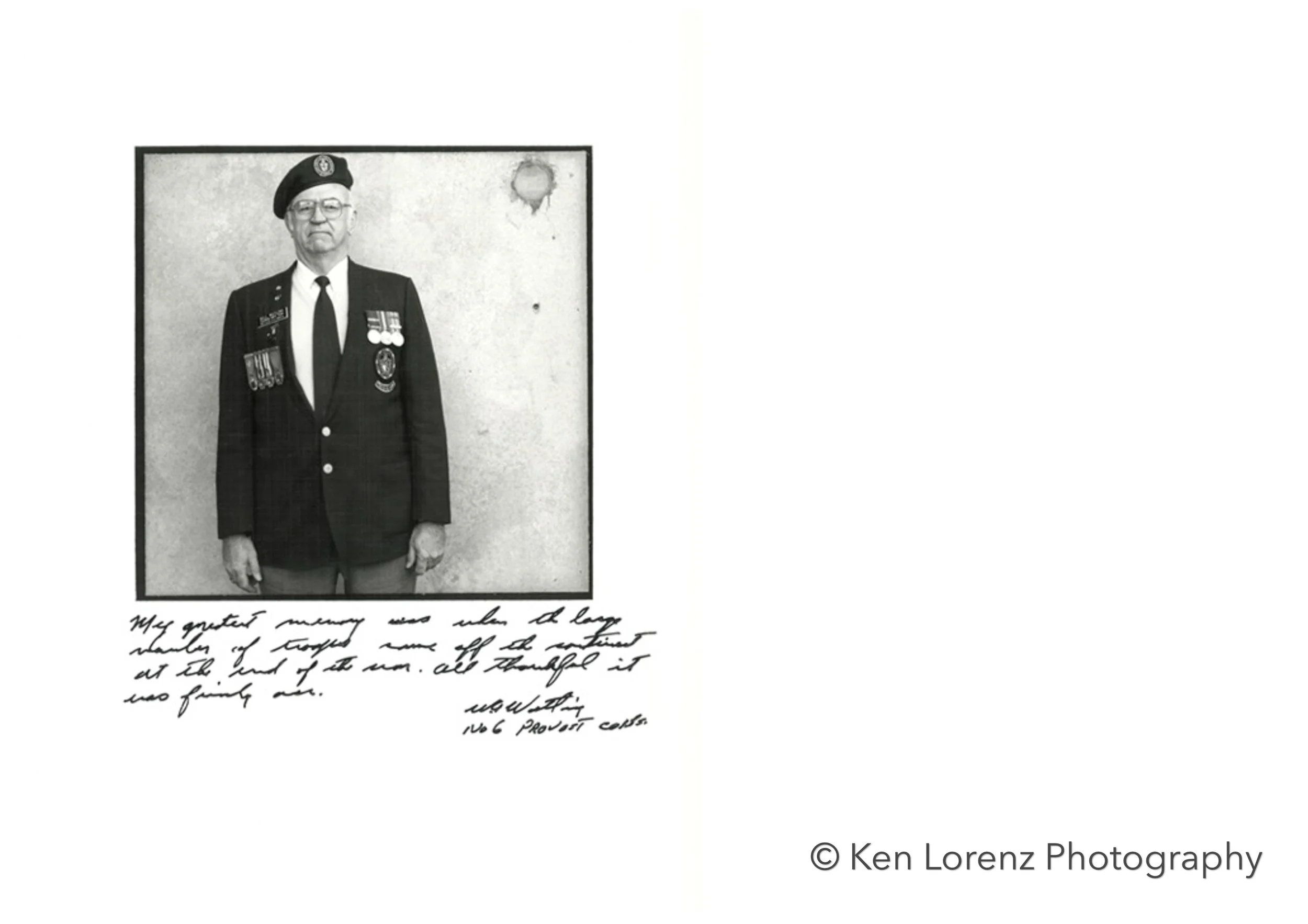

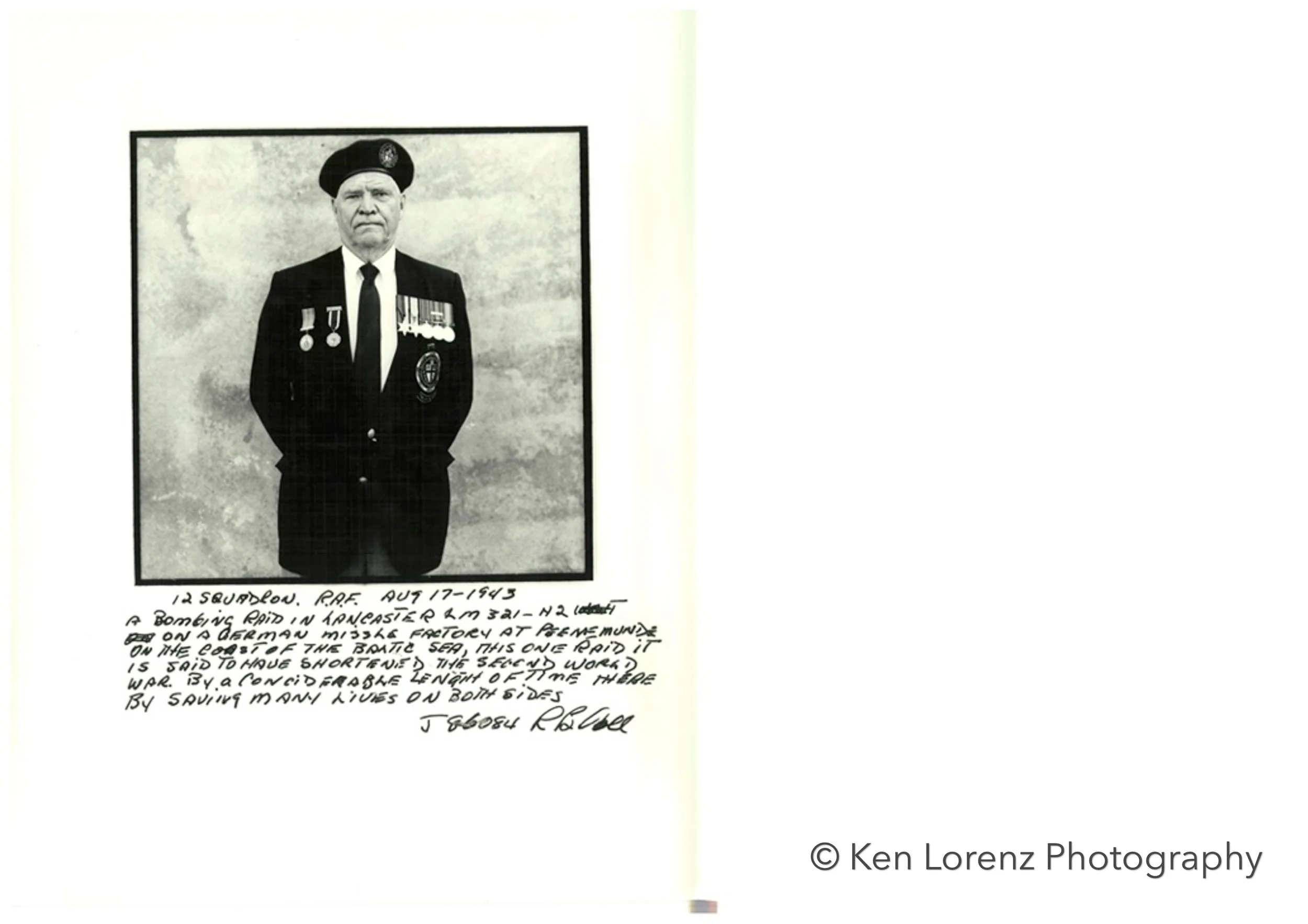

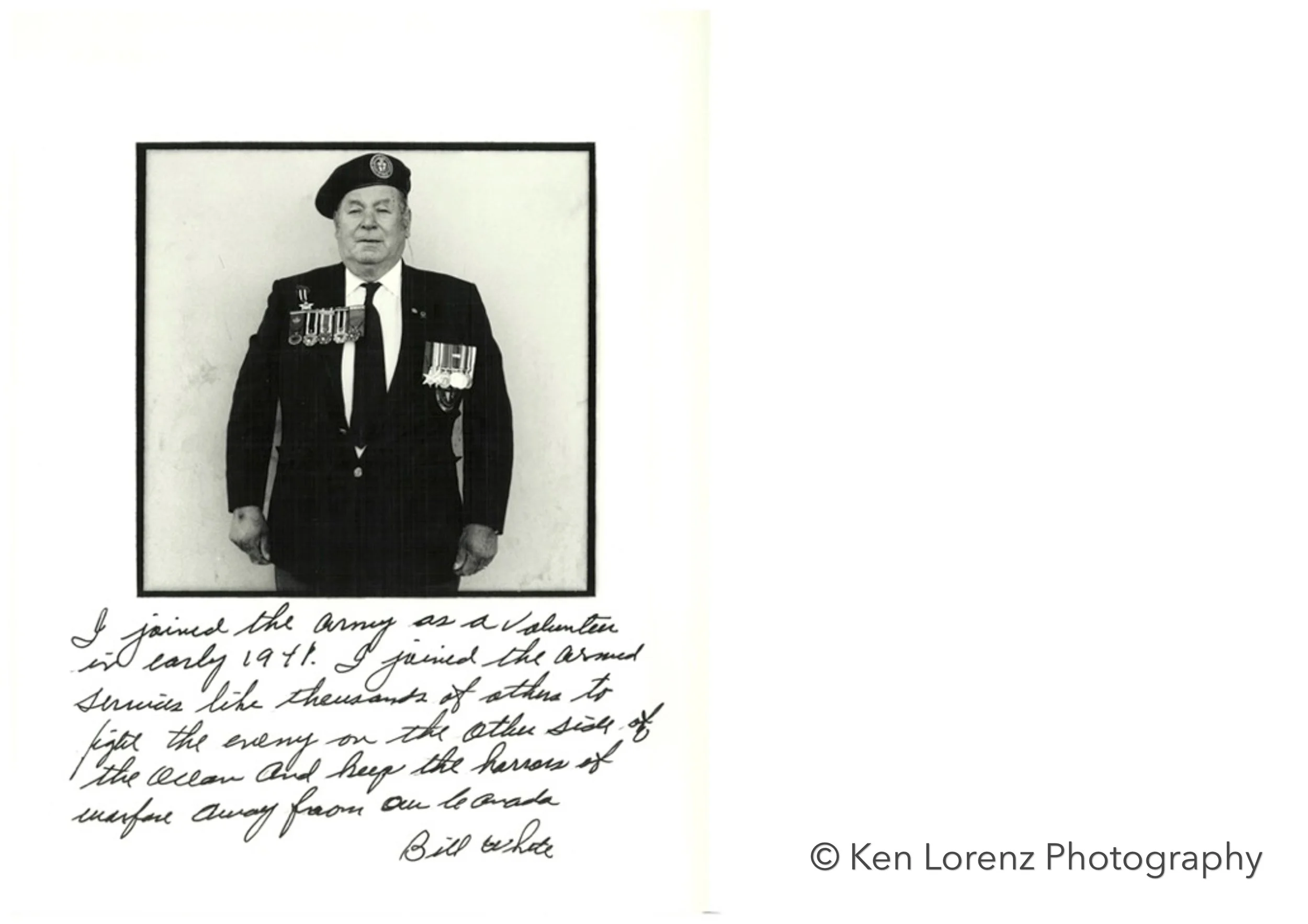

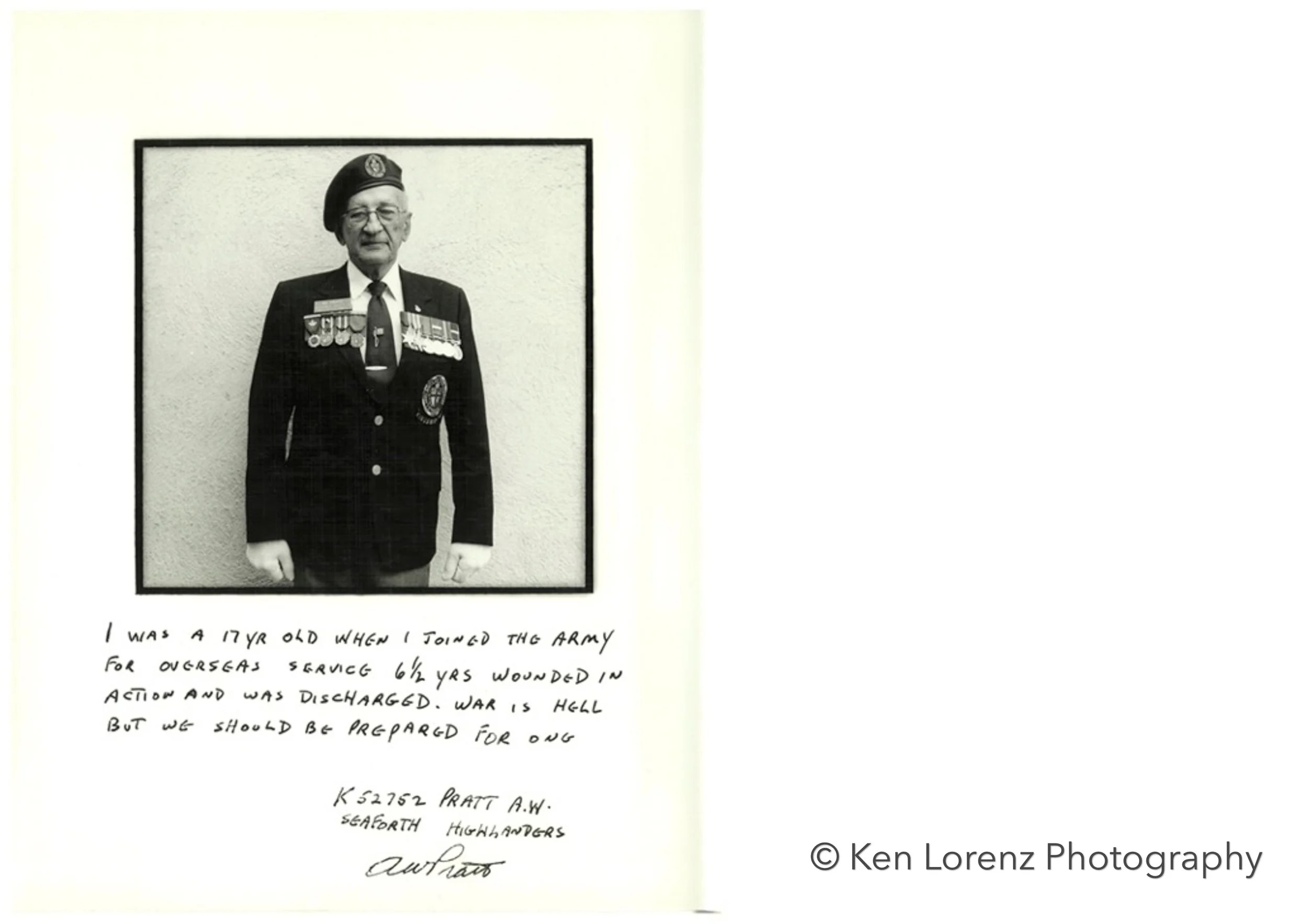

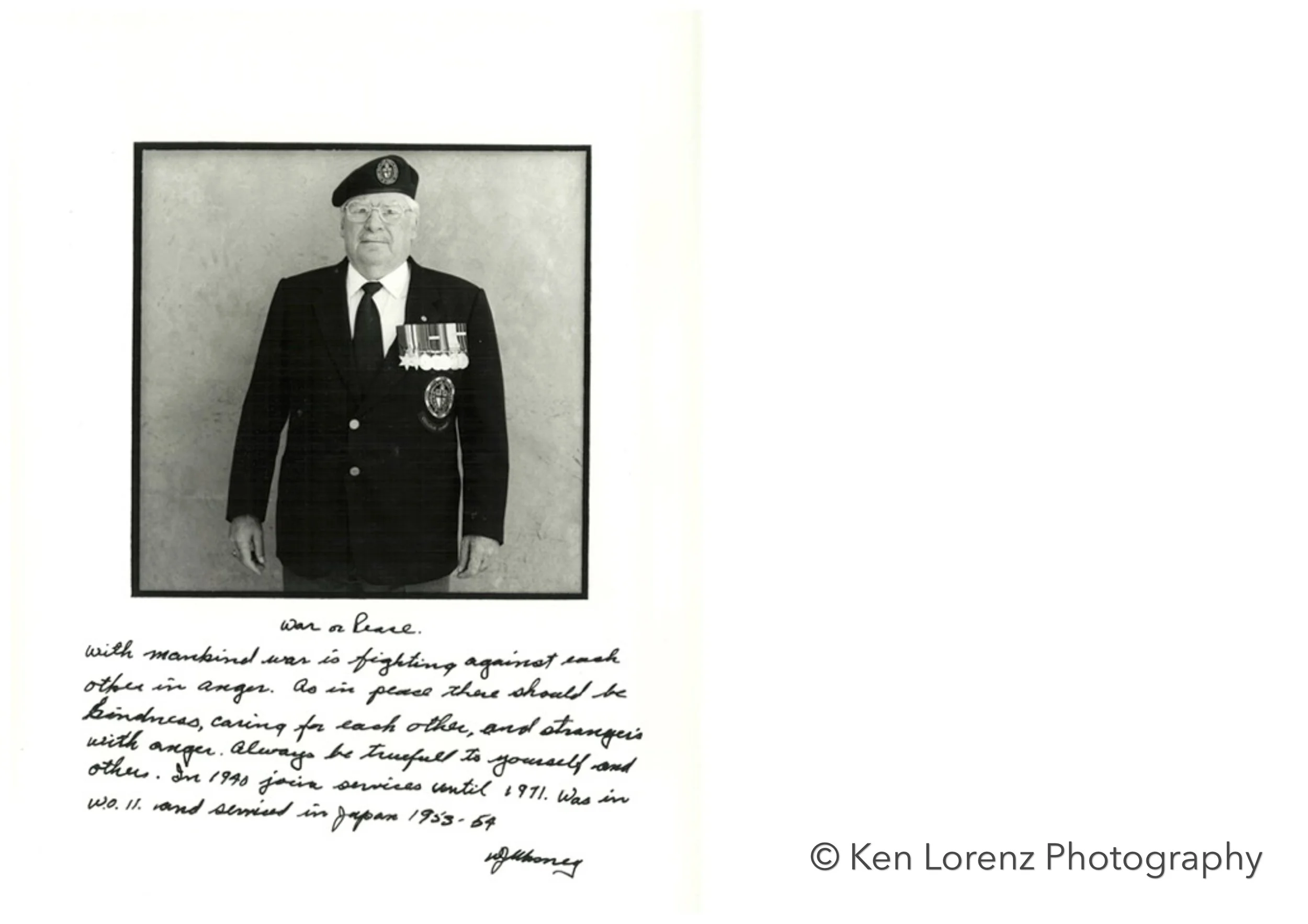

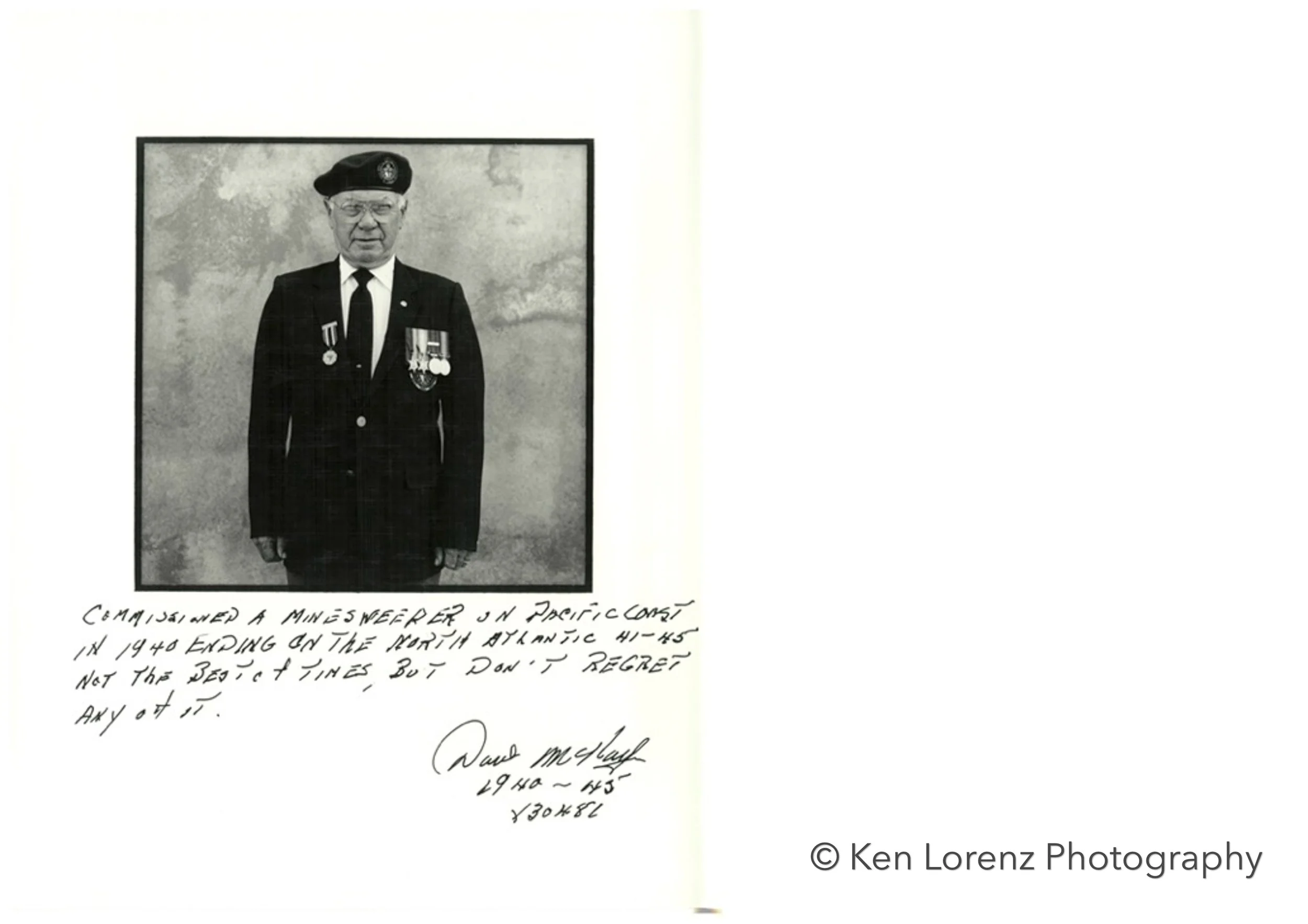

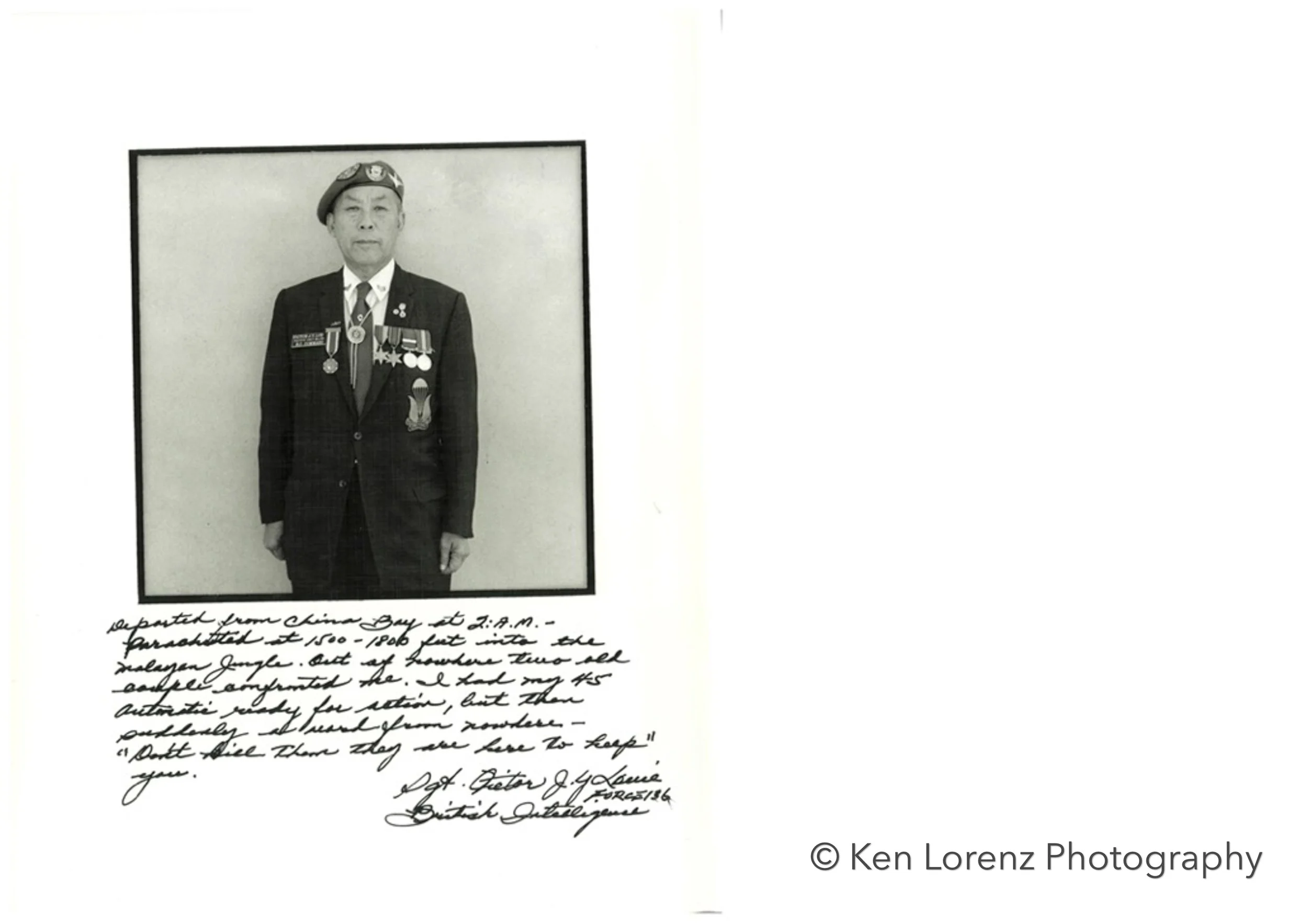

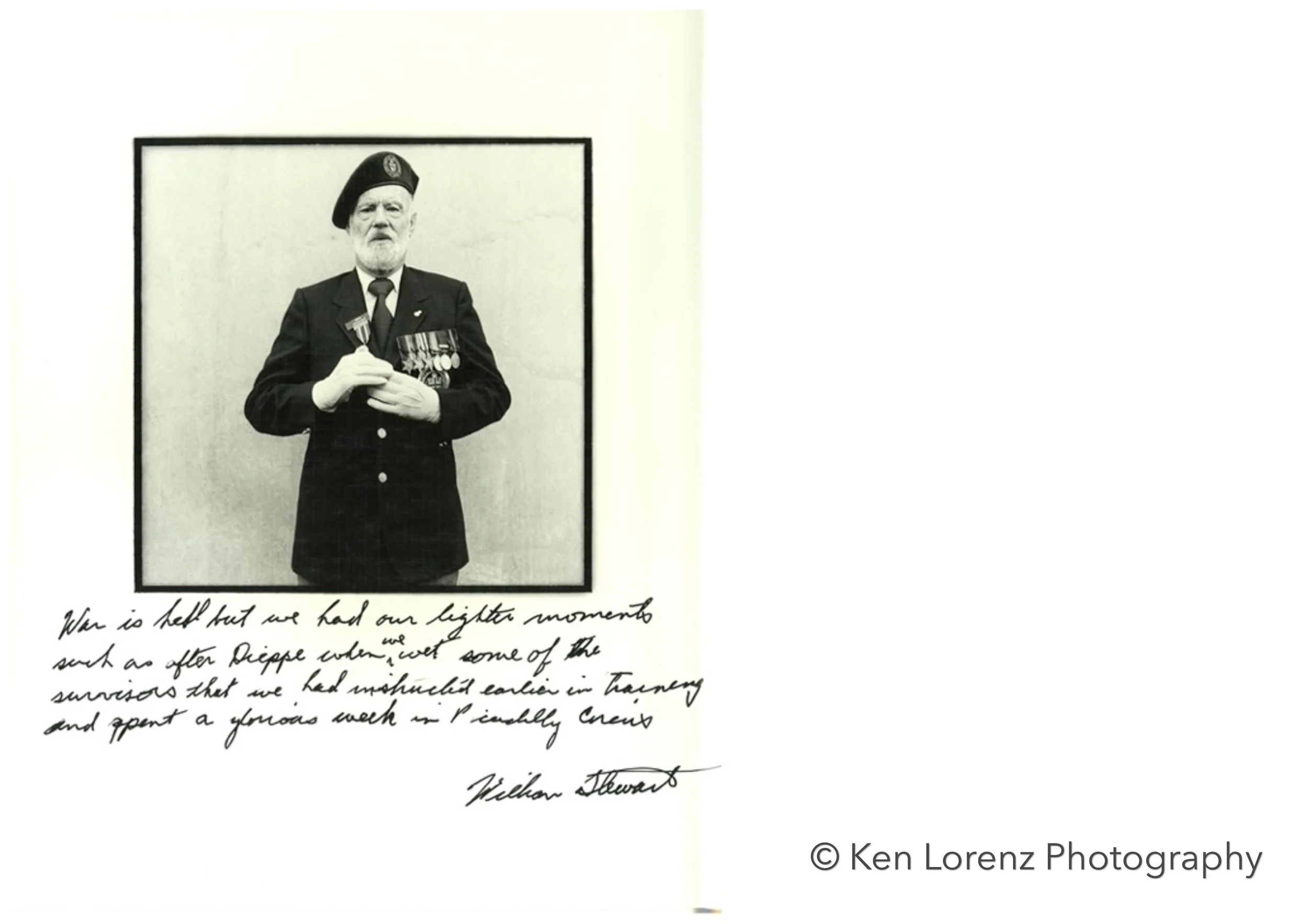

Most Canadians alive today are removed from war. Many of us are fortunate in that our experience of war is and has been indirect, either through historical study of past events or, perhaps at its closest approach, through the reporting in newspapers and television of current but distant events. However, our distance from war is more than spatial or temporal; it is also emotional, and even moral, and this kind of non-physical distance is potentially dangerous. What we fail to derive from history, or even the barrage of exciting but fleeting images of televised news coverage, is the urgency of conflict. There are two, sometimes opposing aspects to this sense of urgency. The first is somewhat abstract and removed from the tumult of day to day living, but it is evident when war presses upon a nation: we feel that our way of life, the democratic and humanistic ideals by which we live, and even the lives of our nation’s people are somehow imperiled; and so we must fight. This was certainly true of the great wars of this century in which Canada participated. There is also a more personal sense of urgency to war, one that is most often felt on the battlefield. Especially true today, this feeling of personal mortal danger is just as real to individual civilians as it is to those doing the actual fighting, but nothing can quite compare to the immediacy of the soldier’s gripping dread as he/she waits to confront “the enemy”. In the heat of battle, thoughts of noble causes and abstract concepts are short-lived when they are those of men who must face fear and death. What cannot be ephemeral, however, is the soldier’s courage, since it is only with courage that the first, abstract sense of urgency can overcome the more immediate second, and it is only with courage that the soldier upholds the principles for which he fights while at the same time fighting. From a distance, it is easy, though still necessary, to question the motivations and choices of nations and individuals waging war, but it is not easy to grasp the urgency that compels the emotional and moral decisions to kill and to be killed. There is today a new urgency surrounding the survivors of Canada’s war experience. Although every November 11 th we pause to remember those who fought for our nation, and especially those who made their ultimate sacrifice, The Canadian war veterans together remain a vigorous institution in this country., and are a daily testimony to important parts of our history. But as Canada enjoys a lasting peace, it is in danger of losing to time this testimony to events that surely helped found that peace. “40 Memoirs” is in part a response to this new urgency, made all the more immediate by the passing of several veterans before their written comments could be etched below their photographs. It is a rare visual document, not of war, but of these one-time warriors. They are the only group of men and women in our society for whom the experience of war is vividly relived in memories, the only people who can communicate from first-hand knowledge its urgency, its terrible impact on human lives, and why it should never come to be experienced by Canadians again; moreover, they are the only ones who can communicate why it was at one time necessary to fight in order to ultimately sustain life. But the prints, composed of a photograph of each veteran in a stylized, strong eye contact pose coupled with a statement of their wartime ordeal in raw, black ink, do more than document an institution: they capture a little of the essence of each man and woman photographed and force the viewer to confront each veteran on a personal level. They declare such a stark and unshielded honesty that when we look a veteran directly in the eyes, as we must when viewing the photographs, we too are compelled to a certain honesty. The prints speak to us and we respond to the voice, and to the face that is behind it, and to the message that the voice and the face convey. The message might be a recounting of a particular incident in the war, or it might be a simple affirmation of the favourite “war is hell” ! If the meaning of these words has been tarnished over time with usage, it is the eyes of the veteran above the words that tell of their true significance. It is the eyes, and the voice, to which we must respond with an honesty that cuts across our political persuasion, and our support for, or enmity towards, or indifference to military institutions and policies. In the end, we can only respond to the individual, and to his courage.